Covenantal Listening

Building common good in Stamford Hill

Many of our communities are deeply fragmented, so how can we build a common good with our neighbours? Father William Taylor tells us a story from his parish which is situated in the heart of an Orthodox Jewish community. He relates a fascinating journey of covenantal commitment to place and finds that the answer to the question is listening: listening to God and to each other.

Before I arrived as the parish priest at St Thomas’ Stamford Hill, over thirteen years ago, I completed a doctorate in Scriptural Reasoning. This practice, whereby Jews, Christians and Muslims co-read their scriptures, had found its way across the Atlantic to the Cambridge Inter-faith Programme. Working with the CIP my research challenge was to set it up in a civic context between community faith leaders.

But how would Scriptural Reasoning work in the back streets of Hackney?

Well, I discovered that in my neighbourhood, it didn’t work at all. Stamford Hill is the heart of the Jewish Charedi community in the UK, and the rabbis I met weren’t remotely interested in co-reading their holy scriptures with me. In fact I found that this particular community was extremely wary of any contact at all with non-Jews.

I knew that it was not meant personally. But still, it was frustrating: barely the only contact my parishioners reported having with their Jewish neighbours were notes received through their letter boxes asking if they would sell them their houses. There wasn’t much joyful celebration of the common good going on here.

Actually, within its own terms and between its own people, the Charedim demonstrate remarkable warmth and solidarity. But you have to know something about their history to understand the reasons for their self-sufficiency and, indeed, for their astonishing growth.

Back when much of the rest of the Jewish world was getting with the programme of the Eighteenth Century Enlightenment, the Charedim feared the compromises that any accommodation with the modern world seemed to demand and they doubled down on their desire for separation. Unlike those in the Haskalah movement, who were open to the new thinking, the Charedim turned their back on the promises of “progress” and the wonders of secular self-determination. They preferred instead to remain faithful to the revelation at the heart of creation on Mount Sinai, as they saw it.

Then came the Holocaust. Having nearly been wiped out, the Charedi community was instead propelled forward by the aftershock of this trauma. Their strength of family and character is extraordinary. It is estimated that within twenty years they will make up the majority of the Jewish community in this country. In Stamford Hill alone there are at least ninety synagogues within a relatively small district known as locally the ‘holy square mile’.

Their lifestyle is strikingly different from the mainstream. Most of the Charedim are opposed to the viewing of television and films, the reading of secular newspapers and books and apart from business use, access to the internet. Indeed internet-enabled mobile phones without filters have been banned by leading rabbis.

So these are some of the reasons behind the Charedim’s resistance to the superficial blandishments of the latest inter-faith initiative. And yet, still, we are neighbours and my church wants to find a way of being neighbourly, something more reciprocal than passing notes through each other’s doors. We prayed and asked “Lord, what will we do?”

Over the years some bridges have been built. I developed a friendship with the late Rabbi Pinter and with Rabbi Gluck we set up the Jewish Christian Forum together in 2013. Despite the sadness of losing him to Covid, the Forum is thriving and has been helpful for talking through local civic matters together. But this only works for the professionals; my parishioners still lament the little contact they have with their Charedi neighbours.

Then a few of us set up Clapton Commons, a non-aligned community network and independent charity. We raised the money to convert a redundant toilet block into Liberty Hall, a new “village hall” on Clapton Common. I was delighted that our relationship with the Charedim was such that a number of the rabbis and leaders cheerfully joined the mayor and the bishop at the launch event in 2017.

Since then, our engagement with the Charedim has been pretty ad hoc. Our kosher coffee offer from our kiosk hasn’t taken off. But they do make use of our bike repair clinic, even though it’s essentially just a service delivery operation like any other.

Clapton Commons and Liberty Hall wouldn’t have happened without St Thomas’ but we couldn’t have done any of it without our neighbours. Although my congregation is small, we feel covenantally devoted to this place. We have a vested interest in the thriving of our area. The kind of Christian leadership I have been called to here feels as much about recognising where the Spirit is at work in the neighbourhood, and building local relationships, as it does about leading liturgy and pastoral care within our church.

So how do we find a way to meet the hearts and enter the imaginations of our neighbours? How do we see the world as they see it? We want to build a common good between our communities. It seems that the key is to be found in listening. Listening to God and listening to one another.

Last autumn, at an open day on the Common, Margaret Browne, our church treasurer, shared her hopes and frustrations with a Clapton Commons volunteer, a designer called Nick Bell. Before retiring, Margaret spent years on reception at the local primary school. Like many of my congregation, she is a Christian from the Caribbean, and she sees how important it has been for young people to tell their story of origin in the context of their family’s faith: and she believes it is the responsibility of the community elders to help them do this. She feels that this could be something that the Charedi women might share. She had been wanting to start a conversation, but didn’t know how it could be done.

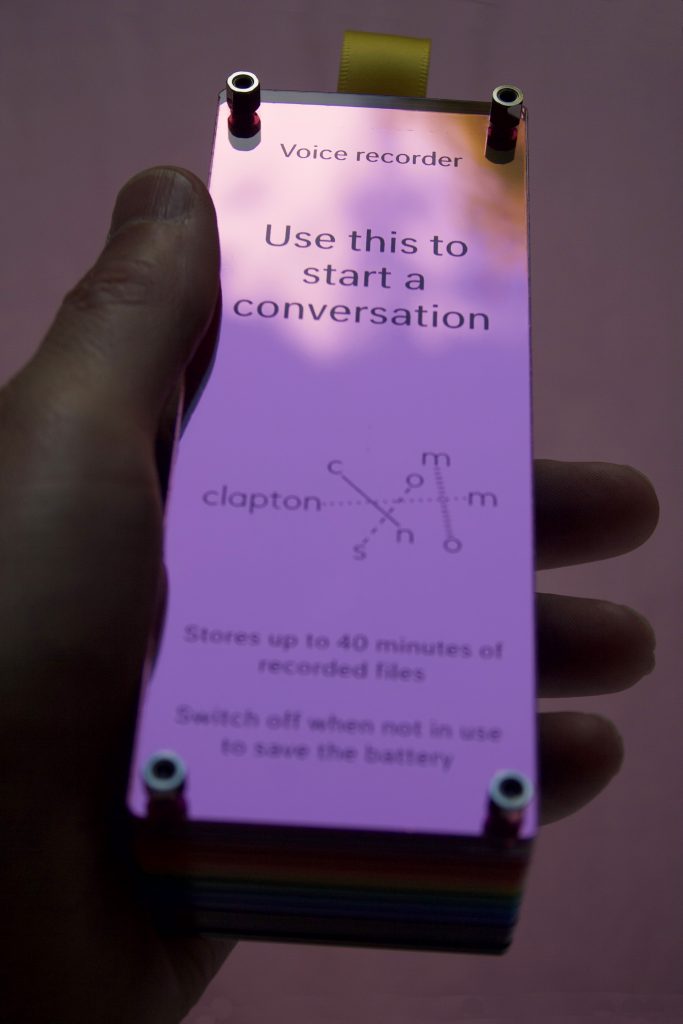

Moved by her story, Nick wondered if there was a way to make Margaret’s wish happen, while respecting her Charedi neighbours’ instinct for separation. He thought of making a recording device that could be passed between representative community members – in the first instance, women elders. It could be left at a designated place – the coffee kiosk, say. And then by arrangement, picked up, spoken into, and passed back, to and fro. The recording could be made easily and discreetly, at home. Neither face to face contact, nor access to the internet, would be required. He wanted to create something that could combine the intimacy of the spoken word with the hermetic seal of the voicemail message, where listening was as important as speaking.

A few months later Nick came up with a prototype. He called it the “chatterbrick”. He hopes it may enable a dialogue shaped by curiosity. Now, we just needed conversation partners.

One of the beautiful things about being a vicar in a Jewish area is that it has made me notice the deep seasonal interplay between our respective traditions. Well, more to the point, I realise the dependence of our liturgical year on the Jewish one. Pentecost, fifty days after Easter, not only marks the birth of the Church when the disciples experienced the pouring out of the Holy Spirit – it is also a Jewish festival.

Shavuot – also known as the Festival of Weeks – is fifty days after Passover, marking the occasion when the Torah is revealed by God to the Israelite nation on Mount Sinai. According to Midrash, Mount Sinai blossomed with flowers, which is why on this festival, Jewish families fill their homes and synagogues with fresh greenery and floral arrangements, especially lilies and roses.

So it has been lovely that, in the run up to Pentecost, the garden around Liberty Hall has been taken over by a local Jewish florist. Chana Greenfield has been selling bunches of roses and hydrangea and peonies and eucalyptus folded into great fistfuls of greenery, especially to her fellow Charedi women who are decorating their homes for Shavuot.

Chana has offered to be a conversation partner with Margaret, and to help her find other Charedi women who are happy to begin this listening dialogue across our communities.

Maybe in all of this there are things for us to learn through the interweaving of our celebration of Pentecost and our neighbours’ celebration of Shavuot:

That as the flowers spread across the mountain, anticipating the granting of the covenant, so our conversations may also blossom. And that they will help us discover more about what it means to be in covenantal relationship with our neighbours. And as we do so, that the Holy Spirit may enable us to speak and listen to one another in the gentle spirit of loving-kindness, just like the disciples of the early church.

God is good. He does answer our prayers, but He does so in unexpectedly gentle ways, and, in His own time.

Father William Taylor

Father William Taylor is Vicar of Saint Thomas’ C of E Church in the London Borough of Hackney and co-founder of Clapton Commons. Follow William’s blog at http://hackneypreacher.com/ or follow him on Twitter at @hackneypreacher.

Photos: @kristinperers and Joel Greenfield

This article was featured in the Pentecost 2022 edition of the T4CG Newsletter.