The editorial from the T4CG Newsletter, Pentecost 2023. To view the full version, click here

Ephesians 6:10-17

The Catholic Social Teaching tradition is sometimes said to be the theology of the Holy Spirit in practice. But despite its depth and scale, more often it is perceived in limited terms, reduced to social action, campaigning, and charitable giving. Few understand its potential. Some fail to see that its politics are non-partisan. Few recognise it as an integral part of evangelisation.

Even fewer consider how it relates to the Holy Spirit. Yet its stated purpose is to build a civilisation of love. Intended for all people of goodwill and emphatically not theocratic, its gift is a gospel-rooted, coherent Christian worldview centred on the human person. Drawing us into the territory of statecraft, it helps us expose structures of sin and conceive of structures of grace.

This is a tradition that consistently describes human beings as having a transcendent nature, made in the image of God: it is in “our nature [to be] constituted not only by matter but also by spirit, and as such, endowed with transcendent meaning and aspirations.” (Caritas in Veritate). That spirit calls us to love: “a person is an entity of a sort to which the only proper and adequate way to relate is love” (Love and Responsibility) and to see the human person “as a spiritual being.. defined through interpersonal relations” (Caritas in Veritate).

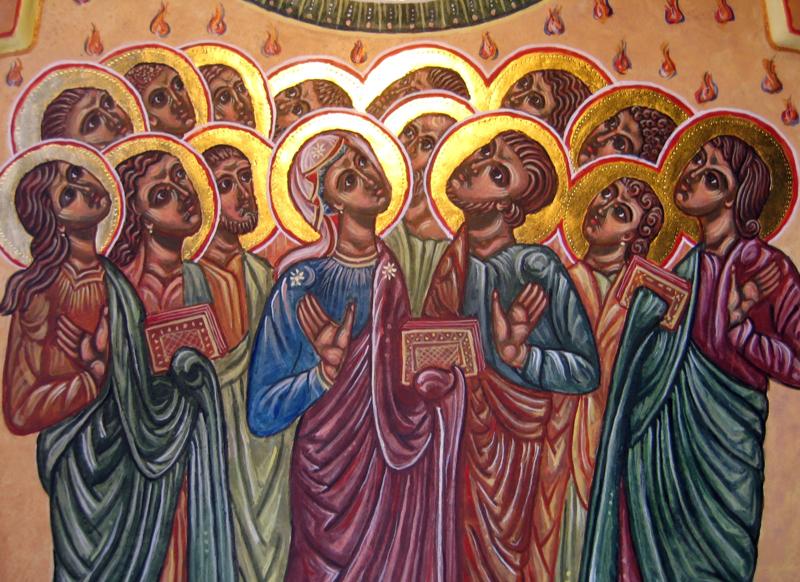

At the first Pentecost, the apostles were overcome by the wind of the Spirit. When God breaks into this young community and dwells among them, they are inspired to develop a simple economy of communion, to become a community who ‘had all things in common’.

This Pentecost, as the latest symptoms of financial dysfunction destabilise more and more families, we can consider the impact of a low wage, high welfare economy on the human spirit. A depersonalised, technocratic system designed around debt generates a vicious cycle that impacts not only the economic but also the social and spiritual.

An economy too oriented to profit, and too little to the common good, promotes intensified consumerism and low wages. The economic pressure generates social pathologies and spiritual malaise, which in turn lead to more welfare expenditure, which brings even more consumerism. As this cycle deepens, we see a dehumanising collusion between the financial system and the technocratic state. The vast commercial interests of big pharma, enabled by governments to exploit human weaknesses and fears, is just one example. In such a toxic symbiosis, power becomes too concentrated. The commodifying, marketising and managerialising practices of these “principalities and powers” play out as an assault on relationship, atomising and dividing us, undermining our common life.

And so these weaknesses of our current economic model ought to be a central concern to people in the churches. As Pope Benedict XVI said: “the economic sphere …is part and parcel of human activity and precisely because it is human, it must be structured and governed in an ethical manner. Thus every economic decision has a moral consequence.” (Caritas in Veritate)

Before the industrial revolution, economies were largely shaped by the relational and by the imagination of God. But our current financial system is shaped by a world that denies God and relies on a false anthropology – two reasons for its inherent instability and its tendency to accelerate the degradation of the human person. Further crises are highly likely.

So why does discussion about the economy feel boring? For most people the economy is like wallpaper, it just is. Change seems impossible. And so well-meaning people default to a politics of low expectations, tinkering at the edges, campaigning against poverty or for increases in welfare, or opening another food bank, inadvertently propping up an unjust system.

It is worth stopping for a moment to ask why the economy seems to be unquestionable. In 1979 we were told “there is no alternative” to the profit-hungry, efficiency-driven, finance-led economy. Money power was separated from human relationships, and a deeply deterministic philosophy became largely insulated from democratic accountability. We were sold the idea that the complexities of the financial system would be better run by technocrats. But the anthropology was wrong and the results were inevitable. The whole thing is unravelling.

We need to break free of those inhibitions and ask questions. Bearing in mind the transcendent, relational nature of the human person and the vast damage incurred, we should be asking “What is this all for?” “Who is it for?” “Why does it generate wages too low to live on?” “Why are nearly five million people parked on benefits?” For forty years the whole British political class, across both main parties, has been negligent, unwilling to rein in the leviathan of global capital, cynically perpetuating the myth of trickle-down economics or doubling down on welfarism. There has been a great theft.

It doesn’t have to be this way. The dignity of work and a just economy must be integral to human flourishing. As Christians with a Pentecost spirit, we cannot settle for less: this is a great spiritual as well as a political battle against dehumanising forces. As Pope Francis has said: “the need to heed this plea is itself born of the liberating action of grace within each of us, and thus it is not a question of a mission reserved only to a few.” (Evangelii Gaudium).

We must ward off the “darkness of this age” by making space for contemplative prayer so we can hear God, who works through us and our relationships. In this way there will be a dialectical, mystical element to our forms of participation: our formations of local association and what we choose to focus on will shape the materiality of the world. The Advocate is here to help us.

In reality, most people want to live lives of love, family, work and relationships. These are the things that generate meaning and purpose and give life in all its fullness. The economy should be designed to go with the grain of human life, not against it. People will accuse us of being idealistic. But there is a will – a “creative minority” of politicians and other leaders who share this worldview. And there is a way – a positive vision that generates hope and generosity – I and my colleagues have written extensively before about the shift from contract to covenant and the politics of grace and place.

This edition of the T4CG Newsletter also includes a brilliant lecture by Adrian Pabst who explores how Catholic Social Thought guides economic reform for the common good. Alongside this there is an interview with Sr Helen Alford who asserts that “social justice”, in its original Catholic meaning, is not an optional extra, but a constituent part of evangelisation.

Further, I would love you to read a beautiful story about a “place of welcome” in the Midlands, by Roy Searle and Alan J Roxburgh exploring ways in which the Spirit is forming new communities of hope. Finally, reflecting on our work with schools, my colleague Jo Stow considers how an openness to the Holy Spirit can prompt a school to become outward-facing and contribute to renewal in its neighbourhood. There is lots more to explore too, just click on the full content link below where you’ll find my latest selection of articles to help you read the signs of the times along with some recommended books.

T4CG is an organic project with several integrated strands. This newsletter gives only a flavour of what we do. Please pray for me and our amazing team, for God’s provision and for all the wonderful partners involved in the work.

Send forth your Spirit, O Lord, and renew the face of the earth. (Psalm 104)

Jenny Sinclair

Founder and Director, Together for the Common Good

Like what you are reading? More inspirational content from Jenny Sinclair can be found here: https://togetherforthecommongood.co.uk/news-views/from-jenny-sinclair

This is just the editorial from our Pentecost 2023 mailing. To read the full content, click here