The question of immigration has become so polarised that honest conversation is inhibited. Many on the right are worried about culture change and national security, while many on the left are troubled by history and disturbed by the plight of migrants. In such a context the bigger questions of political economy, social peace and citizenship are often overlooked. In this short talk for a panel event considering the motion “Should Christians Welcome Stricter Border Controls?”, Jenny Sinclair examines immigration from the perspective of Catholic social thought, weighing the interests of all involved. The debate was held on 6 April 2024 at Trinity Forum London. The panel consisted of Dr Sebastian Morello, Gavin Rice, Jenny Sinclair and Dr Krish Kandiah.

DOWNLOAD Jenny’s text HERE or read on below

Immigration and the Common Good

Good evening everyone. Before I accepted this invitation I did say I wouldn’t fit neatly on either side of the motion. What I’m going to say can be described as a “common good” position.

To do that I’ll draw on the tradition of Catholic social thought, which, just to be clear, is not infallible, doesn’t propose a theocracy. It’s intended as a gift to all people of goodwill.

The common good in this tradition isn’t a compromise or a third way, nor is it utopian. It recognises that, made in the image of God, human beings are relational beings, whose integrity, agency, and their connection with each other, must be upheld. From this Christian anthropology, people must not be subordinated to domination – whether by capital, state, nor by other powerful interests. It recognises context, that human beings have histories, traditions and interests, who, in a modern plural society have to live together, so we talk about building a common good between different groups. It’s sometimes described as a both/and tradition.

In terms of traditions of justice, the common good is not utilitarian, communist, libertarian, it is not liberal, nor is it progressive. It is based on the rabbinical, relational model of justice and virtue ethics that Jesus exemplified, and so it prioritises relationship – with each other and with God.

And so looking at our immigration crisis, a common good position requires us to consider the interests of all the human beings involved, that is those on the move and host populations, and, to do so in light of Christian tradition and within the context of political economy, citizenship and social peace.

Our Story as God’s People

First, emigration is indivisible from the Christian and Jewish story and is integral to the mission of God – it goes to the very heart of our story as God’s people.

Since the 1940s, Catholic social thought has emphasised that migration is part of the human search for the fullness of life and should not be blocked by governments. John Paul II said:

“The task of proclaiming the word of God, entrusted by Jesus to the Church, has been interwoven with the history of Christian emigration from the very beginning… ‘

But – this doesn’t mean open borders.

Borders

Catholic social thought not only asserts the story of God’s people, it also upholds the right of nations to preserve their borders.

Despite his concerns about what he calls “aggressive nationalism”, Pope Francis does affirm the nation state – in fact he laments the “weakening of the power of nation states” due to “the economic and financial sectors, … tend[ing] to prevail over the political.”

So the common good approach affirms the upholding of national borders and the enforcing of a fair migration policy.

Conditions

But it does come with some important qualifications and conditions:

It distinguishes between “necessary and unnecessary migration” – and I quote from a Vatican document here – “Those who flee economic conditions that threaten their lives and physical safety must be treated differently from those who migrate to improve their position.” [1]

With that important distinction in mind, the tradition insists on a raft of humanitarian conditions. This list of conditions is long – too long for me to go through here, but it is based on Matthew 25:40 – ‘As long as you did it for one of these the least of my brethren, you did it for me’ [2]

It insists for example that families should not be divided, it insists on humanitarian corridors, on religious freedom, on the right to work, on decent housing, on help with visas and the justice system – and on integration into society. It summarises these conditions under four principles: welcome, protect, promote and integrate.[3]

The tradition also asserts the right not to migrate. Receiving countries are to partner with sending countries to address working conditions, governance and corruption to disincentivise people leaving.

Theology of Place

So, while it is fundamentally in solidarity with the migrant, in recognizing political reality, Catholic tradition does uphold the right of nations to preserve borders. It does so in recognition of the wider context of political economy, citizenship and democracy, and not least to the theology of place.

In this tradition, our civic inheritance is seen as something fragile, something to be valued and protected. It’s conservative in the true sense.

This means that not only do we welcome the contribution that the migrant may bring – – but we also uphold the particularity of place and the life of the people who dwell there.

The importance of belonging to place is affirmed again and again in Scripture, for example in Acts 17:

26 …he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the whole earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands. 27

We are embodied, embedded relational beings made in the image of God, and love of place is affirmed. For example, Pope Francis says:

“there can be no openness between peoples except on the basis of love for one’s own land, one’s own people, one’s own cultural roots….I can welcome others who are different, and value the[ir] unique contribution…, only if I am firmly rooted in my own people and culture…. [4]

But Francis also asserts the need for roots and belonging, and he condemns the liberal tendency that mocks tradition and cultural attachment:

“There can be a false openness …born of those lacking insight into the genius of their native land or harbouring resentment towards their own people. … We need to sink our roots deeper into the fertile soil and history of our native place, which is a gift of God…. [5]

So building up this common good position, what else should we take into consideration?

Political economy

Catholic social thought calls Christians to stand in solidarity with people who are poor, whether it is our neighbour down the road, or overseas. Jesus loved the poor because in their humility they have a greater awareness of others and of God that the affluent and the busy so easily miss.

Viewing immigration through a race or rights frame is too limited – it can distract us from factors around the economy that are relevant, and some would argue, central.

Catholic social thought has a lot to say about migration but even more about political economy.[6]

Its primary concern is to enable the flourishing of the human person, families and communities, both globally and locally. It critiques any system that is dehumanising – whether the overcentralised state or unconstrained capital. In this sense it is a nonpartisan tradition that is at once both socially conservative and economically radical.

At the heart of this is the dignity of work, the cornerstone of a politics of the common good. Work is more than a way to make a living, it is how we participate with God in the shaping of the world. [7]

A common good requires balance between the interests of capital and labour, and recognizes that work has historically operated through a system of inheritance, with a body of skilled practice passed on through generations.

But over the last forty five years globalization has eroded this inheritance.

This is an important backdrop to understand the migration crisis we now face.

As the economy reshaped to allow capital the freedom to move, and required labour to become mobile, there was a failure to manage the impact at home. Instead of a coordinated strategy of retraining and investment, there was a default to a lazy reliance on the import of people from overseas who were willing to take lower wages. This neoliberal imperative to keep wages low then required higher and higher levels of migration.

And so now we have a low wage, high welfare economy, with increasingly precarious and meaningless jobs rewarded with wages too low to live on, subsidised by the public purse making up the difference. We are drawing skilled low paid workers away from their own countries to prop up our health care services, and meantime we have a shocking 5.2m people on out of work benefits.

We have concentrations of wealth and vastly inflated property prices in our urban centres where the young cannot afford a home and form a family, and a state of civic degradation in our poor, post industrial, urban, rural and coastal areas: a forty five year abandonment, with huge pressure in terms of housing need, health services and schools.

From a Christian perspective, this careless treatment of our own fellow citizens is unacceptable.

It’s into this context that refugees, asylum seekers and economic migrants end up. They too end up on low wages living in poor conditions in poor areas. Again, from a Christian perspective, this is unacceptable.

John Paul II says that the migrant’s “search for work must in no way become an opportunity for financial or social exploitation.” [8]

While it may have made sense on a corporate spreadsheet, the consequences of this hyper liberal ideology on social peace were never properly thought through – nor any mandate sought for the level of immigration it generated. Successive governments have colluded to insulate financial interests from democracy.

This current migrant crisis represents a story of mismanagement on a vast scale. While some have benefited, a very high price has been paid by our poorest communities.

As a result, migrant workers are now seen as opponents, the credibility of genuine asylum seekers and refugees is undermined, and dissent about the level of immigration is silenced with accusations of racism. Legitimate questions of economy are suppressed. Meanwhile the interests of big corporations are obscured and protected.

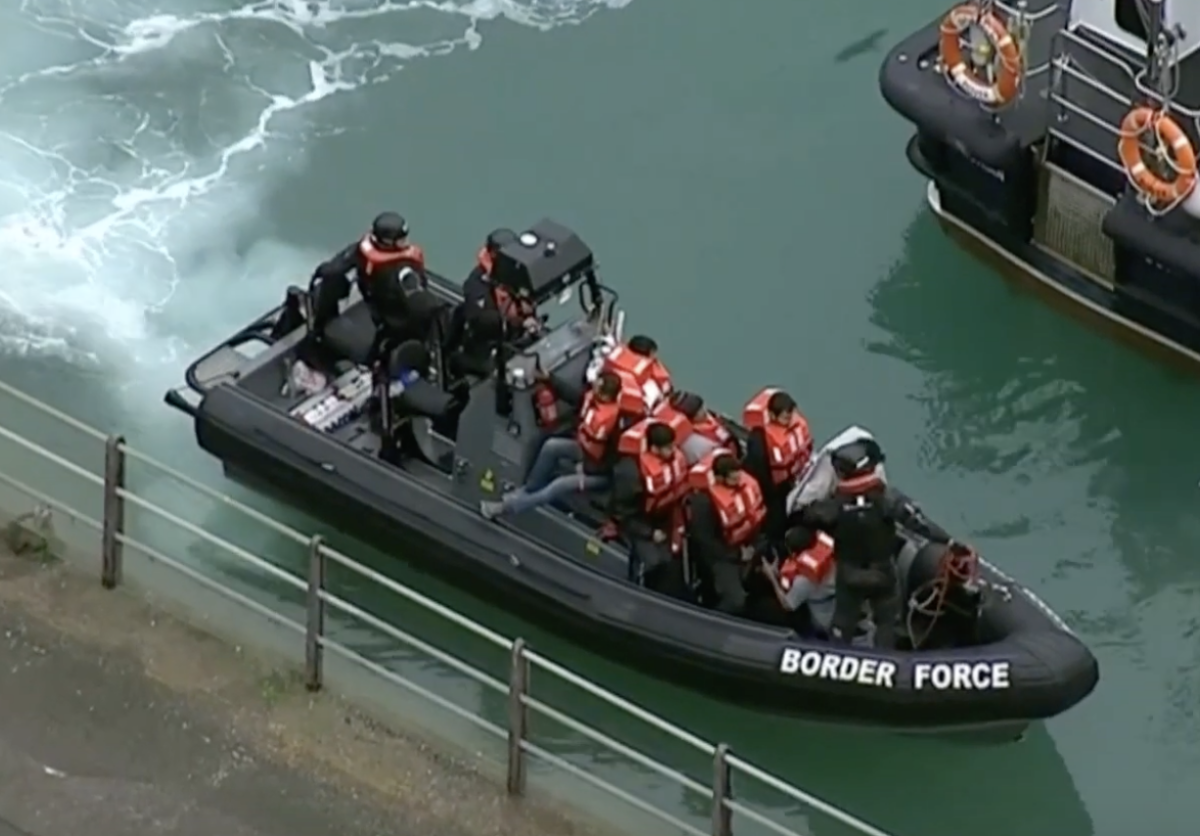

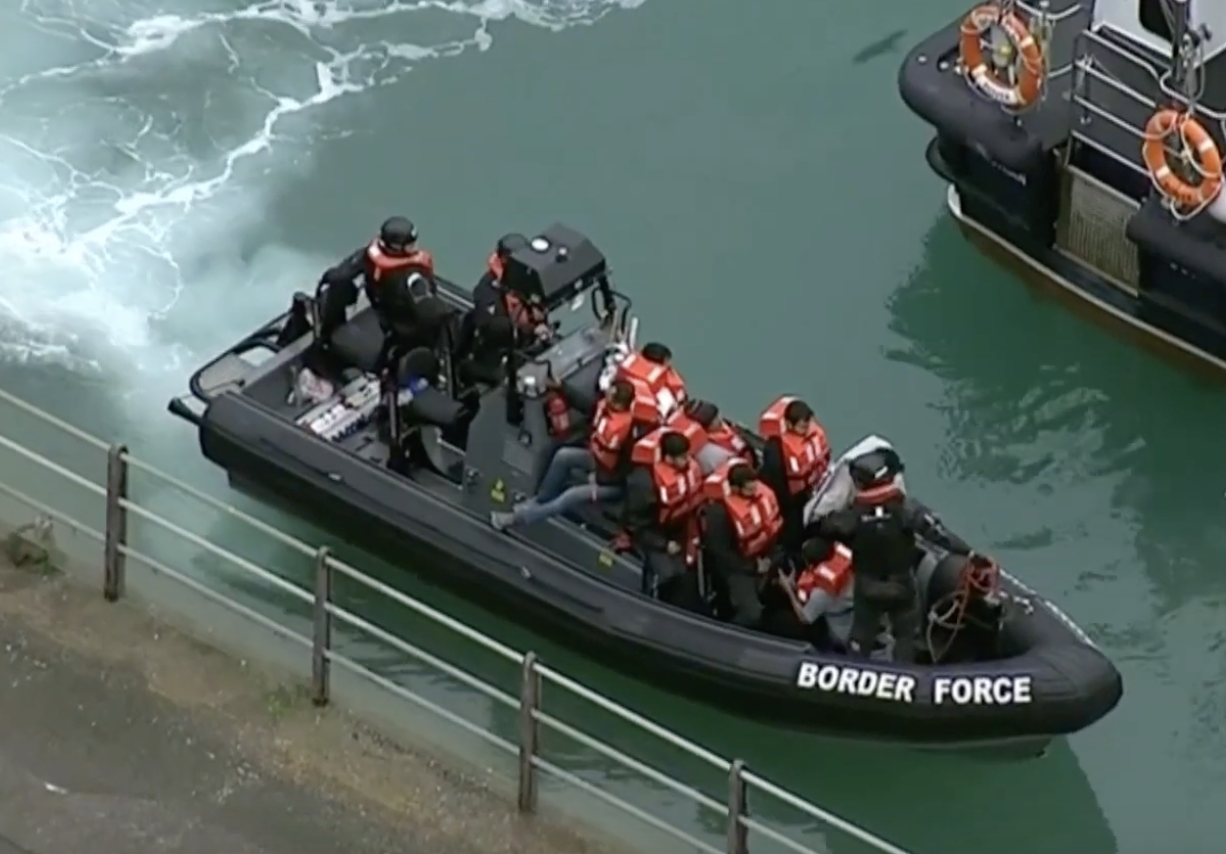

And so immigration has become a lightning rod around which voters feel ignored. Even setting aside the small boats, enormous increases in legal migration proceed without voter consent. People feel the government is not in control of running the country.

Social peace

Catholic social thought has a great deal to say about social peace. [9] It is concerned with the dignity of all human beings and balancing the interests of different groups – both welcoming and protecting refugees and asylum seekers, and requiring the consent of the host community, taking great care not to destabilise the host population.

This tradition has a great deal to say about citizenship and democracy too. When governments fail to address questions of culture and ignore questions of democratic control, social trust is eroded.

People lose faith in the establishment. Fears go way beyond race – the vast majority of the British people are tolerant and generous. Rather, their concerns are around security, livelihood, sovereignty and agency. Subsidiarity, mentioned earlier, speaks to this. Decisions should be taken closest to those they affect. People see their world changing and quite rightly feel decisions are being taken outwith the democratic process.

In fact, immigrants who have long settled here are concerned about who is coming into their adopted home, especially about the failure of certain extremist groups to integrate in some places. When dissent is silenced or met with contempt, disquiet grows.

People often ask me what can be done about the problem of the far right. Well if the concerns of ordinary voters continue to be ignored, then more will go down that road. If the language of compassion and empathy is weaponised to close down dissent, legitimate concerns will be driven underground and result in a politics of resentment.

On the far left, racialized post colonialist and oppressor-oppressed ideologies argue that migration is an inevitable payback for the sins of empire – part of a sea of liberalism that frames open as good and closed as bad, where any constraint – whether on identity, tradition, family, borders or capital – is seen as regressive. These pressures inhibit governments from acting, and in many countries we are now seeing life on the ground becoming destabilised.

This mismanagement, together with the subordination of family, community and place to the interests of big corporations, is undermining social peace.

Christians are always asking how should we respond. Many on the right are troubled by modernity and worry about national security, while many on the left are troubled by history and disturbed by the plight of migrants.

The tragedy is that neither have paid enough attention to the nature of our political economy. They have not acknowledged the extent to which our working class poor – of all ethnicities – have borne the brunt of the profound social and economic changes of the last forty five years.

This negligence by both the Christian right and the left unfortunately results in migrant and refugee rights being seen as a middle class progressive left liberal concern, which provokes a sense of loss and powerlessness – a gift to the far right.

In conclusion

I think it was Chesterton who pointed out the problem of promoting one virtue to the exclusion of all the other virtues [10] – he understood the importance of the holistic both/and position to which Catholic social thought invites us. It requires that we embrace complexity.

So my response is that Christians should support border controls – but as a component part of a carefully thought through strategy that takes account of our story as God’s people, that insists on key humanitarian conditions being met, that is based on an understanding of theology of place, and that all of this is situated within a comprehensive strategy of political economy with a proper conception of citizenship, honouring democracy and a commitment to social peace.

Jenny Sinclair

Founder and Director, Together for the Common Good

NOTES

[1] Pontifical Council “Cor Unum” and Pontifical Council for the Pastoral Care of Migrants and Itinerant People, “Refugees: A Challenge to Solidarity”(1992) (#4)

[2] Gaudium et Spes #27

[3] https://www.vatican.va/content/francesco/en/messages/migration/documents/papa-francesco_20170815_world-migrants-day-2018.html

[4] Fratelli Tutti, #143

[5] Fratelli Tutti, #145

[6] Centesimus Annus

[7] Laborem Exercens

[8] Laborem Exercens #23

[9] Pacem in Terris

[10] GK Chesterton, Orthodoxy [III The Suicide of Thought]

This was included in the Christmas-New Year 2024-2025 edition of the T4CG Newsletter. If you found it meaningful, you can explore more content like it by subscribing to Together for the Common Good on Substack.