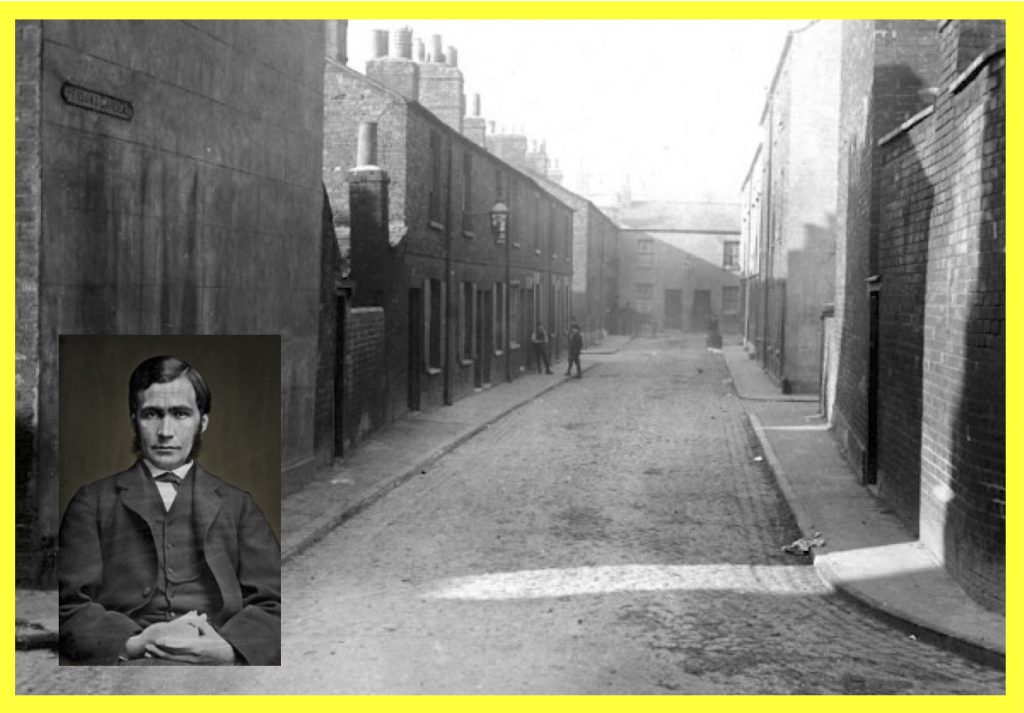

The Victorian philosopher Thomas Hill Green popularised the term “common good” nearly a decade before Rerum Novarum was published in 1891. An unusual Oxford don, he was elected to the City Council and ran evening classes in the slums of St Clement’s. Here Ralph Norman explores how Green’s metaphysics of citizenship posed a corrective to the materialist and individualist ethics in England in the 1860s, and argues that his legacy speaks to our contemporary sense of crisis around the understanding of state, community and individual. Drawing on Aristotelian ideas of civic friendship and viewing education as a means of enabling the development of moral citizens, Green’s particularly democratic vision of the common good influenced political thinkers such as Asquith, Hobhouse, Beveridge and Tawney.

View the footnotes for this essay in another window by clicking here

The Common Good and the Metaphysics of Citizenship: Thomas Hill Green’s Legacy

I

The common good is a moral concern shared by a diversity of traditions. What I want to do here is explore the specific and significant contribution made to common good thinking by the Victorian philosopher, Thomas Hill Green (1836-1882). It needs be remembered that Green’s was an important and critical contribution to thought about the common good – undeniably so – and yet one which is still sometimes overshadowed and obscured, at least in many theological circles, by the subsequent flourishing of Catholic Social Teaching. Let us be clear: Green was no Catholic, and he died nearly a decade before the publication of Rerum Novarum in 1891. And yet Green’s early advocacy of the common good in the late 1870s may stake a genuine claim to being the moment – perhaps the critical moment – that brought new life to modern thought on the common good. Of course, this makes Green’s relationship to later official Catholic definitions of the common good uniquely puzzling. One sometimes gets the impression that those working within the traditions of Catholic Social Teaching have good knowledge of Green, yet are unsure quite what to make of him in theological terms. Meanwhile, political philosophers have produced a largely independent body of critical scholarship on Green’s common good, sometimes emphasising its religious and spiritual aspects, though more often explaining its relevance to secular liberalism and communitarianism. And yet these two traditions of the common good share much between them, overlapping in ways which suggest that they are not mutually exclusive. I happen to think that the similarities and continuities still need further exploration.

Over the last couple of decades there has been something of a revival of interest in Green, not least because of the ways in which his philosophy of citizenship speaks to a contemporary sense of crisis affecting our understanding of state, community, and individual. It is argued that a reassessment of the philosophical roots of the democratic Welfare State takes us back to Green, and if we today need a new philosophy of citizenship, his works can supply inspiration now just as they did for a past generation of political thinkers. And it must be said that in his own time his influence was considerable. R. G. Collingwood reckoned that Green’s impact was largely practical rather than philosophical and extended far beyond Oxford.

The school of Green sent into public life a stream of ex-pupils who carried with them the conviction that philosophy, and in particular the philosophy that they had learnt at Oxford, was an important thing, and that their vocation was to put it into practice… Through this effect on the minds of its pupils, the philosophy of Green’s school might be found, from about 1880 to about 1910, penetrating and fertilizing every part of the national life.[1]

Lists of key figures influenced by Green typically include many of the leading lights of the so-called New or Social Liberalism – as well as some socialists – of the generation stretching from Herbert Asquith and L. T. Hobhouse through to R. H. Tawney and William Beveridge.[2] Many of them viewed education as a particular means of facilitating the development of moral citizens, and took leading roles in the development of the new civic universities then being established across England: R. B. Haldane helped found the London School of Economics as well as Imperial College and also served of Chancellor of both St Andrews and the University of Bristol; H. A. L. Fisher became Vice-Chancellor of the University of Sheffield; Michael Sadler was Vice-Chancellor of Leeds; A. D. Lindsay was a shaping influence for the common good as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Keele. More strikingly, the Oxford University settlement in the East End of London – Toynbee Hall – extended Green’s general approach to the slums of London, bringing university minds into contact with the realities and problems of working-class life. William Beveridge, R. H. Tawney, and Clement Attlee are among some of the better-known names associated with Toynbee Hall in particular. Attlee himself acknowledged Green’s influence on the settlements, as well as the importance of religious agencies in supporting many of them.[3] Later, Attlee would justify state action with reference to the “common good”.[4] Tellingly, this legacy within Labour circles has persisted over the decades. The former Deputy Leader of the Labour Party, Roy Hattersley, thought Green “the only genuine philosopher English social democracy has ever possessed”.[5] Indeed, when during the 1987 General Election campaign Hattersley had been asked about the philosophical basis of Labour, his answer was simply, “T. H. Green”.[6]

Green himself actively put into practice what he taught. He was an unusual Oxford don: the first professor to get himself elected to the City Council and start evening classes in the slums of St Clement’s. What puzzled some of his contemporaries was what this had to do with his lectures on metaphysics. The more perceptive among them suggested that Green’s practical work for the common good was an intrinsic element of his philosophical idealism. The two aspects were combined in a coherent vision of the metaphysics of citizenship. As J. H. Muirhead argued:

What in reality made him the greatest force of his time in the University was just the union in him of these two elements, the citizen and the idealist philosopher – not as accidentally combined in a man distracted between them, but as organically united with each other. To him an ideal was no creation of an idle imagination, metaphysics no mere play of the speculative reason. Ideals were the most solid, and metaphysics the most practical thing about a man. On the other hand, practice was no conventional round of tasks, but the opportunity of giving expression to ideas, of clothing them with substance as we clothe our thoughts in language.[7]

If one wonders why Green thought a metaphysics of citizenship necessary, the answer lies in contemporary needs for a suitable rejoinder and corrective to the materialist and individualist ethics developed in England in the 1860s. Green was intent on countering both Herbert Spencer’s social Darwinism and John Stuart Mill’s individualistic liberalism. For Green, this task evidently required more than just some re-description of human ethical life in non-material terms; an entirely different view of the world was needed. He decided that a metaphysics of ethics was the best answer to Darwin and Spencer. Green’s idealism therefore sought to demonstrate the limits of any natural science of morals with reference to a wider and more substantial metaphysics of knowledge orientated towards what he called the spiritual principle in nature. Idealism was key to understanding ethics, purpose, meaning, life, the world, and the end of all things in the common good. To understand the effort, one has to remember Hermann Lotze’s advice that “the true beginning of Metaphysic lies in Ethics”: we understand that which is with reference to how things should be.[8]

Once Green is understood as an exemplary representative of idealist philosophy in reaction against Social Darwinism, it ought to become clear that his relationship to Hegel is not straightforward. Green had, of course, read Hegel; but he was not a Hegelian. Collingwood suggested it was better to describe Green “as a reply to Herbert Spencer by a profound student of Hume”. Collingwood also said that the other great thinker of the British idealist school, F. H. Bradley, “knew enough of Hegel to be certain that he disagreed with his cardinal doctrines”.[9] Quite clearly, both men inhabited a post-Darwinian intellectual context radically different to that of the earlier German Hegelians, and their version of idealism developed under a different set of impulses and motivations. Following the lead of the Master of Balliol College, Benjamin Jowett, Plato provided the Oxford idealists with a particularly important reference point. (Jowett had deliberately and consciously represented described Plato as the “father of Idealism” in the critical material accompanying his English translations of Plato’s dialogues).[10] A recovery of Aristotle was also thought important. Those close to Green, like his student, D. G. Ritchie, thought Green’s particular project could better be understood as an Aristotelian correction of Kantian ethics.[11] The suggestion is that what Green meant by the common good has a root in Aristotelian ethics, and particularly in Aristotelian notions of friendship. The good of a human person is connected to the good of his or her friends. Indeed, my friend’s good is part of my own overall good and contributes to my eudaimonia. This type of interpretation has recently been confirmed by David Brink’s close analysis of Green’s ethics, published under the rather revealing title, Perfectionism and the Common Good. According to Brink, Green’s metaphysics universalised Aristotle’s otherwise more limited common good.[12] Green himself, it perhaps should be remembered, thought that this conception of a universal common good depended on a Christian notion of the value of all people. The ethical good of different peoples was to be found in one ultimate end, common to all.

Idealism provided a holistic vision: it was a way of viewing all things as parts of a single whole. Victorian idealism did not imply any simplistic dualism of mind and matter. It did not seek to dissolve the world of tangible objects into the shifty mists of rarefied thought. It was no esoteric mysticism. In actual fact, its chief proponents typically argued for a type of philosophical monism. They responded to the needs of reason to understand the world as one intelligible whole, in which matter and spirit, science and art, morality and religion were related as aspects of a single coherent universe. Physical objects remained real things in a real world; but they were also intelligible to mind, related one to another within a single universe of thinkable relations. They could not be thought without reference to consciousness, and consciousness related them to the whole. Green’s point seems to have been that the world as we know it is largely mind-constructed. Moreover, he took mind to be the basis for the unobserved world of values, beauty, and reason. From this Green deduced the existence of a cosmic mind – something like the Stoic Logos – which rendered the universe intelligible and created the objective values of our own moral and rational experience. For some later readers this has proved a metaphysical stumbling-block. Green’s metaphysics of the Eternal Consciousness – like Bradley’s Absolute – was out of fashion, philosophically speaking, for much of the mid-twentieth century. Quite often, Green’s post-idealist critics did not note quite how cautious Green’s account of the Eternal Consciousness had been. But it is fair to say that Green’s cosmic mind nevertheless remained amenable to religious interpretation, influencing figures as diverse as John Macquarrie and S. Radhakrishnan. As Keith Ward has observed, “Though they do not always realise it, people who believe in God are idealists in this sense… I believe that when they realise that, belief in God immediately becomes more rational and defensible”.[13] And it is not just traditionally religious thinkers who have been (or are being!) attracted to this type of idealism. Panpsychic monism is going through something of a revival at the moment. David Chalmers, for example, continues to speculate about the existence of “a fundamental sort of consciousness” underlying reality.[14] Thomas Nagel’s Mind and Consciousness suggestively argues for an avowedly non-religious approach to pansychic monism.[15] And Yujin Nagasawa’s work on both consciousness and the ontological proof provides a third relevant potential conversation partner for the re-working of idealist themes.[16] None of these contemporary philosophers are Greenians, of course. But the signs are that something like Green’s cosmic mind has life in it yet. It was certainly central to Green’s moral philosophy, and it is this ethical aspect of the Eternal Consciousness or Eternal Principle which makes his account distinctive. Time and again we see him connecting religion to morality in particular. As Green himself explained in his Sermon, The Word is Nigh Thee:

if there can be an essence within the essence of Christianity, it is… the thought of God not as ‘far off’ but as ‘nigh’; not as master but as father, not as terrible outward power forcing us we know not whither, but as one of whom we may say that we are reason of his reason, the spirit of his spirit; who lives in our moral life and for whom we live in living for the brethren, even as so living we live freely, because in obedience to a spirit which is our self; in communion with whom we triumph over death, and have assurance of eternal life.[17]

II

Thus far it should be clear that Green’s philosophy combined religious instincts with a metaphysics of citizenship. The key question is what this has to do with the development of common good thinking in particular. To provide an answer it is necessary to examine Green’s own use of the term, “common good”. It is both extensive and comprehensive; it is prominent; it also pre-dates, adumbrates, or anticipates later aspects of Catholic Social Teaching. What I want to suggest is that there is good evidence for thinking that contemporary talk about the common good owes a great deal to Green. In 1902, D. G. Ritchie drew attention to the “conspicuous” recurrence of the phrase “common good” in Green’s political writings.[18] Tellingly, in 1908 J. H. Muirhead also recalled “Green liked to call it… a Common Good”.[19] Quite clearly, both believed that the “common good” was peculiarly and distinctively Green’s language. It was his phrase: he popularised it.

Let me explain with reference to two key works in which Green writes about the common good: his Prolegomena to Ethics (1883) and his ‘Lectures on the Principles of Political Obligation’ (1886).

Both works started life as lectures given in Oxford after Green became Whyte’s Professor of Moral Philosophy in 1877. According to A. C. Bradley, Green lectured on sections of the Prolegomena to Ethics twice.[20] Only one section was published in his lifetime, in the January edition of Mind for 1882. Very soon afterwards, in March of that year, Green died aged just 45. Further sections of the Prolegomena subsequently appeared in the April and May editions of Mind. The complete text was then edited by A. C. Bradley and was published in its first edition in April of the following year, 1883. Anyone opening the book will see that two chapters (Book II, Chapter 3 and Chapter 4) are explicitly concerned with what Green called the “common good”. This was a fundamentally important concept for Green: it represented his answer and reply to the inadequacies of Victorian utilitarianism and materialism. As Maria Dimova-Cookson has said, “the common good complete’s Green’s moral theory”.[21] Human fulfilment was not to be found in utility, but in pursuit of an ideal which ought to be shared by all rational agents. Green gave the following criteria for the common good:

- For the “educated conscience… the true good must be the good for all”;

- “no one should seek to gain by another’s loss”;

- “gain and loss” are to be “estimated on the same principle for each”.[22]

This means that the common good could be realised in different ways in different contexts. And yet each realisation of the common good was always related, teleologically, to the ideal.

Between the most primitive and limited form… as represented by the effort to provide for the future wants of a family, and its most highly generalised form, lie the interests of ordinary good citizens in various elements of social well-being. All have a common basis in the demand for abiding self-satisfaction which, according the theory we have sought to maintain, is yielded by the action of the eternal self-conscious principle in and through nature. [23]

It also meant that education was key: the educated conscience knew that the true good was the good for all. As Alasdair MacIntyre has observed, ‘”Green was the apostle of state intervention in matters of social welfare and of education; he was able to be so because he could see in the state an embodiment of that higher self the realization of which is our moral aim”.[24] The attainment of a good civil society necessitated the development of a collectively shared understanding of the aims of that society. Green suggested that so long as there was inequality of opportunity within society – so long as there was inhibitive inequality of wealth or inhibitive inequality of access to education – the common good was unlikely to be realised. Such inhibitions would need to be ameliorated in order to better facilitate the common good.

Civil society may be, and is, founded on the idea of there being a common good, but that idea in relation to the less favoured members of society is in effect unrealised, and it is unrealised because the good is being sought in objects which admit of being competed for. They are of such a kind that they cannot be equally attained by all. The success of some in obtaining them is incompatible with the success of others. Until the object generally sought as good comes to be a state of mind or character of which attainment, or approach to attainment, by each is itself a contribution to its attainment by every one else, social life must continue to be one of war.[25]

The ideal to which all should aim could be expressed in quite simple terms: “the only good which is really common to all who may pursue it, is that which consists in the universal will to be good – in the settled disposition on each man’s part to make the most and best of humanity in his own person and in the persons of others”.[26] In the Prolegomena to Ethics Green developed this idea of “an absolute and a common good” as underlying both moral duty and legal right.[27] As his use of “I and Thou” language indicates, Green’s “common good” also had a personal idealist dimension to it.[28] Green’s ideal was not only humane, but expansive: he saw that there was “an ever-widening conception of the range of persons between whom the common good is common”, and that the common good ought to be the “object of a universal society”. It made a claim “of all upon all for freedom and support in the pursuit of a common end”.[29] Green’s common good certainly had a specifically Christian root, for he admitted that “We convey it in the concrete by speaking of a human family, of a fraternity of all men, of the common fatherhood of God; or we suppose a universal Christian citizenship, as wide as the Humanity for which Christ died”. But this was also transferred and extended “under certain analogical adaptations” to “those claims of one citizen upon another which have actually been enforced in societies under a single sovereignty”.[30]

R. L. Nettleship dated the Lectures on the Principles of Political Obligation to 1879-1880.[31] They were first published first in Nettleship’s edition of Green’s Works, Volume 2 (1886), and subsequently in a stand-alone edition prepared by Bernard Bosanquet.(1907). This is where things get very interesting for any serious student of the history of the common good. Green used the exact words “common good” seventy-eight times in the Lectures on the Principles of Political Obligation (on average, once every 2.8 pages in both Nettleship’s and Bosanquet’s editions). I am not here counting related phrases or variations on the theme such as “good in common with others”, “good for self and others”, “common wellbeing”, “social good”, “public good”, “higher good”, “final good”, “good conceived as common” or even “good as common”. All of these also occur in the text, but none of them so frequently as “common good”. The words “common good” are repeated time and again by Green. It seems incontestable that Green’s work was the “language event” which initiated technical use of the phrase “common good” in English idiom.

What Green had to say was that we ought to obey the State only insofar as it aims at realising the common good. A rational agent’s positive freedom to realise their good life in common with others meant that there was a rational, common good basis for citizenship. Green’s argument was not politically absolutist. Although he maintained that the State had a right to promote morality (insofar as this also promoted the common good), he also maintained that the citizen had rights against the State whenever the State acted against the common good. Quite clearly, the common good was not conceived as something already fully realised in history, but as something constantly being sought. If you read the Lectures on the Principles of Political Obligation alongside the Prolegomena to Ethics it becomes apparent that the “I and Thou” element of Green’s thought supplies an interpersonal element to conceptions of the common good. Green’s common good is not a closed concept, but one marked by openness.[32] One of the leading authorities on Green’s thought, Colin Tyler, has argued for a “pluralist dynamic” in Green’s common good thinking. Tyler even suggests that “there can be as many equally legitimate conceptions of its requirements as there are conscientious active citizens”, suggesting that Green’s was a particularly democratic vision of the common good.[33] As Henry Jones, explained, “a form of government and a mode of life in which a whole people seeks a common good… is alone a true Democracy”.[34] Or, as Avital Simhony has argued, it is important to recognise that Green’s form of the common good was “complex”, lying “between liberalism and communitarianism”.[35] The common good is an ideal we are always seeking to realise; how we do so in any given context nevertheless remains a matter for constant agonistic debate and critical testing.

Green’s works were published in an era when Britain was slowly working its way towards modern democratic norms. The Principles of Political Obligation opened the floodgates for a cascade of “common good” language in late Victorian and Edwardian philosophical writing. Without seeking to providing an exhaustive survey it is useful to pick out some indicative examples of Green’s influence on moral and political philosophy. In 1892, Green’s student, J. H. Muirhead, devoted a chapter of his University Extension Lectures on The Elements of Ethics to a discussion of “The End as Common Good”.[36] In 1899, Bernard Bosanquet used the phrase “common good” forty-five times in his influential Philosophical Theory of the State.[37]In 1920, Henry Jones used the phrase twenty-six times in The Principles of Citizenship.[38] Turning to Leonard Trelawney Hobhouse, “common good” occurred no less than seventy-five times in The Elements of Social Justice (a book which subjects the idea to vigorous and thoughtful criticism).[39] Following Green, the “common good” established itself as a characteristic feature of social and political philosophy in Britain.

From what source did Green derive the language of the “common good”? Although he undoubtedly did more than anyone else to revitalise and popularise the phrase in Victorian Britain, it clearly did not originate with him. There is, for instance, an isolated example of the “common good” in Charles Darwin’s The Descent of Man (1871).[40] Close attention to the sources cited in Green’s footnotes does, however, help suggest some credible answers to the question of where the English phrase “common good” came from. Green was a critic of Locke, and would clearly have known Locke’s argument that the legislative and executive power of a state “can never be suppos’d to extend farther than the common good”.[41] In turn, Locke himself seems to have derived his own fleeting use of the words “common good” from the earlier work of the Anglican theologian, Richard Hooker. Such, at least, is suggested by Locke’s own footnotes.[42] Green, too, knew Hooker’s argument that law is established through the consent of the people. Like Locke, Green also referred to Hooker’s Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity I.10 to substantiate this point.[43] All the signposts therefore point back to Hooker. In the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity, Hooker had described the “common good” as the end or goal of a people’s consensual agreement to live together: such consent, he said, formed “the Law of a Commonweal, the very soul of a politic body, the parts whereof are by law animated, held together, and set on work in such actions, as the common good requireth”. In this way, societies were “instituted” for the “common good”.[44] Hooker believed law without such “consent” was “no better than mere tyranny”.[45] This is an important point. For one thing, it makes Hooker the originator of the English phrase, “common good”. For another, it should be noticed that Hooker’s early version of the social contract (if it was one) was very clearly different to the later one of Hobbes. The contract was to be made, not through fear, but because of the common good. The “social contract” was here closer to a voluntary covenantal oath binding together an Anglican polity. That’s where the English phrase “common good” comes from.

There is something more to be said here. Green’s student D. G. Ritchie once acknowledged the influence of Hooker’s “quiet meditations” on the development of later conceptions of social contract.[46] So much confirms that Victorian idealists were indeed looking back to the sources I have just described. But Ritchie also acknowledged that Hooker was himself here reliant on Thomas Aquinas. This is perhaps not too surprising for Hooker, as an Anglican, located himself within the natural law tradition and at one point called Aquinas “the greatest among the School-divines”.[47] Ritchie had learned from Richard William Church’s editorial notes on Hooker that the relevant language used in the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity bore the stamp of Aquinas’s general definition of law as “that which is ordered to the common good”, “ordinem ad bonum commune” (S.Th. I-II, Q. 90, Art. 3).[48] The “common good” was, then, Hooker’s English translation of Aquinas’s “bonum commune”. That was the source. But it was Green who took it up and promoted the “common good” as a technical term of modern political philosophy.

III

It should already be fairly clear that British Idealist philosophy was developed in conversation with Scottish, English, and Welsh traditions of Christianity. The Master of Balliol, Benjamin Jowett, was an ordained clergyman. The fathers of T. H. Green and F. H. Bradley had been priests of the Church of England and both had grown up within specifically Anglican cultural contexts. And yet Green could hardly be described as an orthodox Christian. I have written on the theme of Green’s religion elsewhere and it need not delay us too long here.[49] It suffices to say that although he was often personally admired by his more traditionally religious students at Balliol, they often felt a gulf between his type of faith and their own. The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, for one, remembered that he “always liked and admired poor Green. He seemed to me upright in mind and in life”. Unfortunately, Green had fallen “on Knox and then on Hegel and he was meant for better things”.[50] Green, in turn, was equally perplexed and concerned at Hopkins’s own decision to join the Jesuits, writing “A step such as he has taken, tho’ I can’t quite admit it to be heroic, must needs be painful”.[51] In Green’s view, Hopkins’ ecclesiastical partisanship risked separatism from the social order and failed to take seriously civic duty and political obligation. Above and beyond this, there were other profound theological differences. Green’s own idealist interpretation of Christianity was both deeply immanentist and deistic. He said he had “faith [in] the new Christianity”, which, “because not claiming to be special or exceptional or miraculous, will do more for mankind than… its ‘Catholic’ form… has ever been able to do”. Far better, he argued, for the rationally “educated conscience” to speak authoritatively than the priests of the Church.[52] In Green’s religious writings,transcendence was reduced to a kind of self-completing immanence of the human self: the Divinity of perfected humanity. Vernon Bogdanor has described this “new faith” as a “gospel of citizenship”.[53] Alasdair MacIntyre, similarly, has accused Green of “trying to produce a new religion… a new version of humanistic Christianity”.[54] Quite clearly, the theological reception of his ideas was to be cautious and critical.

Yet Green’s language of the “common good” was quite quickly taken up by a number of Anglican theologians. Most prominent of these was Henry Scott Holland (1847-1918), who had once been one of Green’s favourite students at Balliol College in the 1860s.[55] Although Green was apparently frustrated by Holland’s decision to become an Anglican priest, the latter’s social theology bore the noticeable imprint of Green’s social theory.[56] In a sermon preached in St Paul’s Cathedral on 27th July, 1890, Holland proclaimed that “social laws” should be directed towards the “common good”. “The individual must be freed… for the sake of the better work he will do for the community”.[57] In an earlier sermon, preached in Green’s own lifetime, Holland had already been seeking to view community life in London in terms of its “common welfare”.[58] Later, in a volume of sermons published in 1906, Holland had continued to associate the “common good and the public welfare”.[59] In Holland’s view, “Fellowship [was] of the essence of Christianity”, and Christians had a duty to apply this ideal to the “welfare of the Community”, making it “ready and applicable to the common good”.[60] Yet for all that Green influenced Holland as a social theorist, Holland remained obdurately resistant to his old teacher’s immanentism and deism. He believed that the good which the idealists sought was to be found, ultimately, in Christ.[61] A number of Holland’s sermons went out of their way to affirm the reality of the Gospel. As he explained in a piece written for the journal he edited, Commonwealth:

When you have come to the end of all that you can know about the divine immanence in man, you will still be in need of the word that will tell you why the divine immanence is so precious and effectual. The divine immanence points away beyond itself. Its religious value lies in its perpetual witness to the divine transcendence. Out of the play of the one into the other springs the eternal significance of the Incarnation.[62]

Scott Holland led the way in the orthodox reclamation of Green’s “common good” by Anglican theologians. He once acknowledged that although Green “gave us back the language of self-sacrifice”, his social theory nevertheless had to be fused with “our own Christian language”, the language of Sacraments, of belief in the Word made flesh, “in the depth and intensity of significance disclosed by faith in the Incarnation”.[63]

Like Green, Scott Holland practiced what he preached. He was an influential figure in the so-called “Liberal Catholic” movement in Church of England, a noticeable advocate for the early Independent Labour Party, and a founder member of the Christian Social Union (1889). He was also the leading influence on the important volume of theological essays, Lux Mundi (1889) – another early source which made use of the language of the “common good”. J. H. Campion’s essay in Lux Mundi on “Christianity and Politics” affirmed that since political authority was “a trust to be undertaken for the good of others… as a ministry for God and man”, any government “which has for its aim anything else than the common good is, properly speaking, not a government at all”.[64] Building on Hooker’s principle of consent, Campion further argued that “Democracy is best adapted to a grave and temperate people, public-spirited and willing to make sacrifices for the common good”.[65] This democratic common good was presumably intended to echo Green. Interestingly, it was supported here with a further reference to the “common good” described in Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical letter Immortale Dei (1885). “Common good”, at least, was how Campion translated the Latin into English for the Anglican readers of Lux Mundi. It is interesting to note how seemingly non-technical phrases taken from the encyclical were represented using formally recognised technical terminology taken from Green’s political philosophy. I will return to this point shortly.

The Anglican “common good” was not in competition with the idealist one; the two overlapped, often with shared aims and goals. When Charles Gore, the editor of Lux Mundi, edited another volume of essays on Property: Its Duties and Rights (1913), the list of contributors included L. T. Hobhouse, Hastings Rashdall, A. D. Lindsay, and Henry Scott Holland. Several of them made mention of the “common good”.[66] Another Lux Mundi writer, Edward Talbot, elsewhere wrote of the “ideal of common welfare and mutual service”.[67] Slightly later, W. H. Moberly (son of the Lux Mundi essayist, R. C. Moberly), writing in the 1912 volume of Anglican essays, Foundations,asserted that “It is self-surrender to the common good which is self-surrender to God: duty to neighbour and duty to God are, in essence, indistinguishable”.[68] Such Greenian, civic instincts were later to be applied by Moberly as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Manchester from 1926 to 1934. So much fitted with the spirit of the age. For much of this time, as A. D. Lindsay explained, idealism was the dominant philosophical movement in England, ““safely… established” in social psychology, economics, and sociology.[69] Lindsay thought Marxism, which he called “a theory of society which denies the possibility of a will for the common good and therefore the possibility of political ideals”, to be easily countered by “the modern idealist school… [which] gave us a theory of the state based on the importance and reality of social purpose”.[70]

Common good thought also worked its way – ostensibly via religious associations – into the language of Suffrage movements in the Edwardian England. Scott Holland based the charter of the Church League for Women’s Suffrage (CLWS) on Anglican incarnationalism: “Christianity is the proclamation of the Divine entry into History; of the Divine submission to the historical conditions of human experience; of the Divine sanction given to the things of time and the affairs of earth, to the body, the home, the city, the nation”.[71] In 1910 the pioneering campaigner for the ordination of women, Maude Royden – a friend of Scott Holland, and Assistant Preacher at the City Temple, London – deployed the language of the common good in her own mission speeches for the CLWS: “The question of the enfranchisement of women is… a great human question, since it concerns the right of women to develop the full stature of their humanity; to find scope for all the powers that God has given them, subject to the common good”.[72] The recognisably Greenian themes of moral human flourishing and positive freedom were never far from Royden’s early feminist theology; they are, for instance, noticeably apparent in one of the books she published in 1922, Sex and Common Sense.[73]

With W. H. Moberly, another contributor to Foundations was William Temple (1881-1944). Temple was also a product of Balliol College, having been an undergraduate there from 1900 to 1903. Edward Caird’s idealism had a profound effect on the young Temple, and many of his works can only properly be understood with reference to the philosophical worldview of contemporary idealism. One has to have read Green, Caird, and Bosanquet to fully grasp the critical worth of Temple’s philosophical theology. Temple also took much from Scott Holland, whom he remembered (in the book where he first used the phrase, “Welfare State”) as the fountainhead of “a massive and coherent philosophical theology”.[74] Much like Holland, Temple contended that idealist philosophy (with which he was largely sympathetic) found its true fulfilment in Christian theology. Where Green believed in the Eternal Consciousness, Holland and Temple believed in the God revealed in Jesus Christ. Christ was the true ideal of humanity already realised in history, the focal point of what Temple called a “Christo-centric metaphysics”.[75] These themes were worked out at length by Temple in his great works of philosophical theology: Mens Creatrix (1917), Christus Veritas (1924), and Nature, Man and God (1934). Predictably, the Greenian “common good” also worked its way into Temple’s mental framework and appeared with regularity and consistency in his published works. From as early as The Nature of Personality (1911), Temple was arguing that a properly educated, self-regulated, self-determining rational agent ought to will the “common purpose” or “common good” for the whole community.[76] The common good also appeared in Personal Religion and the Life of Fellowship (1926).[77] Likewise, in a series of papers published in Essays in Christian Politics (1927), Temple linked the Christian social principles of liberty and fellowship to the free pursuit of the “common good”.[78] It is found again in Thoughts on Some Problems of the Day (1931).[79] So, too, Nature, Man and God (1934).[80] The Hope of a New World (1942) contained more uses “common good”.[81] Finally, one ought to observe the use of “common good” in Temple’s much-valued classic, Christianity and Social Order (1942).[82]

So, the words “common good” once featured regularly in British political discourse, and found a special religious home in Anglican social theology. Moreover, much of this was down to the impact of Green’s lectures from the late 1870s and early 1880s. The question remains, however, what this has to do with the “common good” in Catholic Social Teaching. We have seen that Green derived his English “common good” from Richard Hooker, and that Hooker in turn was supposed by the Victorians to have taken it from Thomas Aquinas’ Latin “bonum commune”. It is perhaps unsurprising, then, that the traditions of English and Latin Christianity shared something in common when they used this key phrase. Certainly, the writers of Lux Mundi (1889) read Pope Leo XIII’s Imortale Dei(1885) as a “common good” document, and translated the relevant sentence from Latin to English accordingly. But in contrast to the Anglican liberalism of Lux Mundi, Immortale Dei actively condemned liberalism. It signifies a stage in Catholic Social Teaching which was not yet fully committed to democracy.[83] There is a question, then, whether the Latin used in this encyclical letter resonated with the same set of meanings that the “common good”, after Green, then carried in English.

Taking a closer look the two Papal encyclicals, Immortale Dei (1885) and Rerum Novarum (1891), it is possible to make a few relevant remarks on the Catholic “common good”. Of course, the latter document, Rerum Novarum, marks a famous new beginning in Catholic Social Teaching, and its use of phrases such as “communi bono” and “communibus boni” may be compared with Green’s English terminology. The first thing to say about both these Papal texts, however, is that the “common good” is less prominent in the Latin originals than English translations might suggest. No particular phrase from the Latin texts is consistently translated into English as “common good”. In point of fact, in these encyclicals of Leo XIII there seems to be no single specific Latin phrase which equates directly, with the same technical precision and regularity of use, to the “common good” in English. Given the subsequent prominence of the “common good” in later Catholic teaching this fact may come as some surprise to the English reader. It seems appropriate to suggest that the “common good” only emerged as a semi-technical or semi-formal term at some later stage in the development of Catholic Social Teaching; in the 1890s, its usage in translation seems rather more experimental.

After writing the preceding paragraph I have subsequently read Anna Rowland’s excellent account of the Encyclical tradition in her new book, Towards a Politics of Communion (2021). She explains that neither Rerum Novarum nor Quadragesimo anno offered any clear definition of the “common good”. She finds it curious that “they offered no real explanation of what they assumed this term to mean”.[84] In her view, one has to wait for John XXIII’s Mater et magistra (1961) for a clear definition. She also adds that the “common good” was “neither a central nor a systematic idea” in the thought of Thomas Aquinas.[85] It seems to me that such views only strengthen the claim that T. H. Green’s consistent and coherent philosophical use of the term marks the beginning of something new. Without Green’s signal contribution, would the “common good” have become what it later did? Rowlands evidently knows that Green drew on Aquinas.[86] The question is, should Green be credited with being the first to treat the common good in a systematic manner?

When did Catholics start using the English phrase, “common good”? Further work needs to be done to answer this question. In July 1891, Cardinal Manning published his prefatory essay, “Leo XIII on ‘The Condition of Labour’”, which accompanied the Latin text of Rerum Novarum in The Dublin Review. When translating “debet enim respublica ex lege muneris sui in commune consulere”, Manning wrote, “it is the province of the commonwealth to consult for the common good”.[87] This was nearly ten years after Green’s death, and two years after the appearance of the English “common good” in Lux Mundi. Manning certainly knew of Green, for he had once written a private letter to Gladstone complaining of the “Hegelianism” being taught at Oxford. Manning had, of course, himself long before been a student at Balliol, and in later life he occasionally visited the Master of the College, Benjamin Jowett. Was his use of “common good” an accident of translation? Or was it deliberately selected to echo contemporary English (i.e., Greenian) use?

This is indeed something of a puzzle. But the perplexing fact is that current Catholic Social Teaching does not only mirror and shadow Green’s language of the common good. It also appropriates other keywords from the British idealist lexicon, too. The “concrete universal”, we are reliably told by Robert Stern, “is particularly associated with the British strand in Hegel’s reception history, as having been brought to prominence by some of the central British Idealists”.[88] Its appearance in works of Catholic theology therefore needs some explanation. The use of this term by the English translators of Romano Guardini and Hans Urs von Balthasar without any apparent critical engagement with the British idealist tradition that lies behind it, [89] means that the typical reader of English might be left puzzled by appearance of the “concrete universal” in the writings of both William Temple on the one and Pope Francis on the other.[90] Of course, there is a common German root here in Hegel, yet Catholic scholarship nevertheless tends not to engage with or contest the particularly heightened prominence given to the “concrete universal” by British idealists in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One may of course speculate that the influence of Green, Bradley, and Bosanquet on the Italian idealists of the early twentieth century helps explain this. But more work needs to be done here.

To conclude. The evidence suggests that Thomas Hill Green did more than anyone else to popularise and promote use of the English phrase, “common good”. He did so in advance of Rerum Novarum, and this explains why some of his Anglican interpreters can be found using the language of the “common good” before their Catholic contemporaries did. Following Green, the “common good” was used with notable frequency by his fellow idealists, and from them it passed into general use in British politics and political philosophy. When the generation inspired by Green was replaced by the next, use of the phrase seems to have dwindled. But this does not diminish its particular historical association with Green. If anything, it actually enhances it. Meanwhile, Catholic Social Teaching has developed its own language of the “common good”, and at least since the Papacy of John XXIII has done so with increasing systematic and technical precision. Although this trajectory of common good thought follows a different line of development to the earlier idealist phase, the two clearly overlap. Both, for instance, look back to Thomas Aquinas for inspiration. And any reasonable reading of the two traditions show they share much in common, not least the notion that people live together for the good of all; not through fear, but because of a Divinely inspired and natural human inclination to want to do good for neighbour. Behind this, I believe, lies an older notion of covenant which reaches back to the ancient Israel – but for this see the work of the late Jonathan Sacks.[91] The common good is genuinely shared by a diversity of traditions. It exists so long as it is inclusive. Long may it last.

© Ralph Norman

FOOTNOTES accompanying this essay are available to download in a pdf here

Dr Ralph Norman is principal lecturer at the School of Humanities and Educational Studies at Canterbury Christ Church University. He is subject lead with overall responsibility for Theology as well as for Religion, Philosophy, and Ethics.

T4CG is pleased to endorse a new MA programme in Religion and the Common Good at Canterbury Christ Church University. The course is suitable for everyone interested in faith in action in today’s world, whether those working in vocational professions, graduates of Theology or Religious Studies, teachers of RE, leaders in faith schools, employees of charitable organisations, or those called to religious ministry or chaplaincy. Full details here: https://www.canterbury.ac.uk/study-here/courses/religion-and-the-common-good