This address was given on 12 September 2011, at a conference on the theme “The Future for Inter-Faith Relations”, held at the University of Birmingham during a Day of Celebration and Thanksgiving to mark the Tenth Anniversary of the Birmingham Faith Leaders’ Group, 12 September 2001 – 12 September 2011.

I am very pleased to be back here in Birmingham and to have the opportunity of addressing this meeting on the subject of the future for inter-faith relations.

I am particularly pleased to be here on 12 September. How well I remember this day 10 years ago, which, effectively, was my introduction to the work of inter-faith relations here in Birmingham.

On this morning, ten years ago, a phone-call was received in Archbishop’s House asking if I could go, more or less straight away, to the Central Mosque were there was to be a show of public solidarity, by the faith leaders in the City, for the Muslim community. I was not able to do so, but my Private Secretary, Fr Timothy Menezes went on my behalf.

This public gathering, on the steps of the Mosque, was the initiative of the late Rabbi Lionel Tann who had learned that the Mosque had receive a number of threatening and abusive phone calls in the aftermath of the terrorist hijacking of three airliners and the terrible destruction they wreaked. He was determined that the Muslim community should not be left alone. The gathering was an important one because it gave impetus to the meetings of the Faith Leaders Group here in Birmingham, giving them shape, character and focus. It started, and it remained, a group based on personal relationships, building personal and communal solidarity and growing in its capacity to respond to difficult and sensitive moments.

I rejoiced to be part of it. I treasure those memories. I salute its on-going achievements.

I remember well, for example, our shared efforts to promote Religious Education, both within this Education Authority and at a national level, too.

I remember our difficult discussions and moments when controversy surrounded the performance of a play by a Sikh author which gave offence to that community.

I remember our efforts to establish an inter-faith fund for the benefit of children in Iraq in the aftermath of the invasion. What a symbolic effort that was, drawing in the generosity of Christian, Jew and Muslim.

I remember the difficulties and discussions we had when world-wide controversy broke out about a small part of the speech given by Pope Benedict in Regensburg. It was a fruit of our relationships that in Birmingham no trouble ensued, rather a respectful acknowledgment of the Pope’s right to speak as he thought best and an attempt, rather better than elsewhere, to look carefully at what he actually said.

I remember with deep emotion an event in the Singer’s Hill Synagogue when I was able to present a precious Torah Scroll and in which I was invited to address the Congregation. I also recall a memorable visit to the Central Mosque for Friday Prayers and lunch. And there was an outstanding seminar on spiritual themes in the Sikh Gudwara on the Soho Road.

I remember with particular satisfaction the remarkable partnership between the Faith Leaders’ Group, Birmingham University and the City authorities in staging a three sided exploration of the role of faith in the modern city. This remains a pioneering venture.

These are precious memories and, I believe, point to a bright future for inter-faith relations not only here in Birmingham but also elsewhere, even in places were such foundations are not in place, and such rich memories are not shared.

Another source of hope for me rises from the Visit of Pope Benedict XVI to the United Kingdom just one year ago. This source gives rise to two springs.

The first concerns the role of religious faith in our society; the second is more particular to the inter-faith agenda itself.

You may recall that before the Papal Visit there was a period of rather virulent criticism not only of the Pope in particular but also of the whole project of faith in God. In contrast to that public and often mocking attack, a single, consistent theme was put forward, as being the basic theme of the Pope’s visit. It was this: that faith in God is not a problem to be solved but a gift to be discovered afresh.

My view is that, one year after the Visit, there is much wider acceptance of that proposition than there was at that time. I believe there is a shift in public opinion, a recognition that belief in God, and all that it brings, is an enrichment and not an illusion, a contributor to society and not simply a problem.

There are, I think, two reasons for this. The first is the cry of necessity; the second the clarity of argument.

In recent months there have been moments and events which have suggested strongly that as a society we need to be clearer and more robust in the key values we wish to uphold. Institutions have been seen in their weakness – and there is no institution which is without weaknesses. And that weakness is the weaknesses of their members. We have seen the weakness of some Members of Parliament, of some professionals in the Media, of some members of the Police and of some people in our cities who chose to create and exploit a moment of chaos for personal gain. The illegality and immorality of all these actions are shocking. They have given rise to that cry of necessity: we can do better than this; we have to find and strengthen our core values.

Along with this experience there have been many words spoken, urging us all to think more deeply about those key values and virtues and how we educate young people into responsible citizens.

These, of course, were the very questions put by Pope Benedict in his Address in Westminster Hall one year ago. He urged us to recognise the need to hold onto objective moral values as the foundation even for our democracy itself. He argued that reasoned discussion can help us to formulate such principles and values. And he demonstrated how important in this task is the partnership between reason and faith. I quote:

The Catholic tradition maintains that the objective norms governing right action are accessible to reason, prescinding from the content of revelation. According to this understanding, the role of religion in political debate is not so much to supply these norms, as if they could not be know by non-believers – still less to propose concrete political solutions, which would lie altogether outside the competence of religion – but rather to help purify and shed light upon the application of reason to the discovery of objective moral principles. This ‘corrective’ role of religion vis-à-vis reason is not always welcomed, though, partly because distorted forms of religions, such as sectarianism and fundamentalism, can be seen to create serious social problems themselves. And, in their turn, these distortions of religion arise when insufficient attention is given to the purifying and structuring role of reason within religion. Without the corrective supplied by religion, though, reason too can fall prey to distortions, as when it is manipulated by ideology, or applied in a partial way that fails to take full account of the dignity of the human person. Such misuse of reason, after all, was what gave rise to the slave trade in the first place and to many other social evils, not least the totalitarian ideologies of the 20th century. This is why I would suggest that the world of reason and the world of faith – the world of secular rationality and the world of religious belief – need one another and should not be afraid to enter into a profound and ongoing dialogue, for the good of our civilisation.’

This, to me, is a huge encouragement and guidance for wider recognition of the role that faith communities can place in fashioning a more stable, principled, just and compassionate society.

But this somewhat abstract statement has been eloquently illustrated in events.

During the riots in August, for example, there were many moments in which the richness of the faith communities delivered vital correctives and action. Clergy were on the streets trying to calm and correct. I heard of one priest who was able to direct young boys back home, preventing them from picking up looted goods lying on the street and thereby risking life-changing arrest and prosecution. Churches and religious centres acted as focal points for those who wished to express their desire and determination for peace and solidarity with the victims of damage. And here in Birmingham was the most well-known example of all: the words and actions of Mr Tariq Jahan. As we all know, in the very heart of a grievous family tragedy, he was able, on the basis of his faith, to summon and express great concern for others. Rather than express an understandable anger his appeal was eloquent and effective: ‘Today we stand here to call to all the youth to remain calm, for our communities to stay united. This is not a race issue’ he said. ‘The families have received messages of sympathy and support from all parts of the communities, from all faith, all colours and backgrounds.’ His appeal was direct and passionate: ‘I have lost my son. If you want to lose yours step forward, otherwise calm down and go home.’

This is faith in action, in its depth and dignity, a major contribution to our common good. And it has been seen and understood by so many. To Mr Jahan can be addressed the words of Pope Benedict, from a year ago, when he expressed the Catholic Church’s appreciation for ‘the important witness that you bear as spiritual men and women living at a time when religious convictions are not always understood or appreciated.’ The witness of Mr Jahan, and of many others, is becoming more readily appreciated. His virtue shows that faith in God is part of the solution, not part of the problem.

The second spring, from which we can draw refreshment, is the encouragement that has been given to interfaith dialogue itself.

In his address one year ago to members of all of our faiths, Pope Benedict reminded us that we must not only act side by side but also come together face to face. He reminded us of the different dimensions of this dialogue. He pointed to the need for the dialogue of life, of action and of formal conversations.

The demands of these dialogues have been spelt out in an article by Archbishop Fitzgerald. A Birmingham man himself, Archbishop Fitzgerald was previously President of the Pontifical Council for Inter-Religious Dialogue in Rome and now serves as the Pope’s Ambassador in Egypt. He shows how such dialogue demands of us ‘a balanced attitude’: one which turns away from stereotypes but which also acknowledges real differences. Dialogue requires a ‘sincere religious conviction’: one which is comfortable in the tenets of one’s own faith and ready to give an account of them. And it requires ‘openness to truth’: truth as something we seek, something by which we want to be possessed, not something which we believe we already possess as our own.

The article also presents the obstacles to be overcome in this process of dialogue: the sociological factors, many arising from the tensions which go with minority-majority relations. This is where the global experiences of faith are so important, for they mean that every faith lives in some places in a majority situation, and in others in a minority one. And in our dialogue we must not only learn about these different experiences, and learn from them, but we must also keep very much in mind the reciprocity which is due to each other whatever the situation we are in. As we know only too well, intentions and actions in one part of the world cannot be held to be separate from those in another.

In this dialogue we also have to work hard at overcoming the burdens of the past which so often feed into another difficult task: that of overcoming suspicions about each others’ motives. These are difficult and substantive tasks, but I believe we are increasingly ready for them. As our own Bishops’ Conference stated in its recent document ‘Meeting God in Friend and Stranger’, the effort to reach out in friendship to followers of other religions is becoming a familiar part of the mission of the local church and a characteristic feature of the religious landscape.

I return to the Inter-faith event of the Papal Visit for my concluding remarks.

The first is this: the inter-faith event which took place at St Mary’s University College in Twickenham was not simply a meeting with the Pope of faith leaders. It was that. But it was much more. It was a meeting of people of our different faiths who play leadership roles in so many different walks of life: sport, the police, academia, politics, enterprise and industry. The very make-up of the meeting was an assertion that people inspired by their faith make a crucial contribution to the leadership of our society, in so many different ways. It was a way of saying, loudly and clearly, ‘We do do God!’

This, I believe, is a marker for the future. There must be a place in our inter-faith endeavours for bringing together similar groups of people so that we can explore the practical contribution that faith makes to leadership for the common good. The venture here in Birmingham, in partnership with the University and the City, is a key example, and one to be further developed and expanded.

Secondly, for our future, it is important that we note that, at that event, Pope Benedict gave central place to the importance of the spiritual dimension of life itself. This, he insisted, is fundamental to our identity. This is the central witness we are to give.

Importantly, he stressed that an emphasis given to the spiritual is not one which devalues other fields of human enquiry and endeavour. Rather, he said, it gives those other endeavours a context which magnifies their importance, pointing beyond their present usefulness towards the transcendent and their part in the greatest quest of all.

Indeed the Pope spoke of this spiritual quest as being for the one thing necessary. And he spoke of it as an adventure. This gives us the right frame of mind in which to go forward together: we are engaged together in a quest which is an adventure. Nothing is more important; nothing more exciting. Together we seek the mystery of God, rejoicing in the gifts we know we receive in our faith, for me the great mystery of Christ Jesus, and generous in wanting to share that gift, while utterly respectful of the gifts of others, which we know will contribute to our human endeavour.

I thank you for your attention. I thank Birmingham for the leadership it gives in these matters. I assure you of my prayers and good wishes for all that lies ahead.

© Vincent Nichols

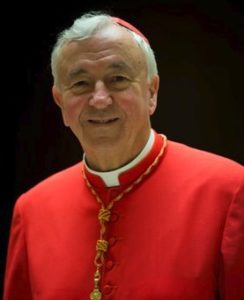

His Eminence Vincent Nichols is the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster and President of the Catholic Bishops’ Conference of England and Wales.