Disruption and the Common Good

As Covid-19 turns our world upside down, we are disorientated and many are suffering. But our deserted streets are also flowering with examples of kindness and solidarity. The crisis is also exposing the failings of a system that has exploited and dehumanised for too long. In this meditation, Professor Wayne Parsons sees signs of hope, and drawing on the experience of the Israelites in the wilderness, he believes this moment could be the impetus for a new political settlement, for the Common Good.

Finding the Common Good flowering in the wilderness

Looking back at my life, I thank God for the many times when my best laid plans were disrupted. As Christians we should be open to times when our lives are turned upside down. As Acts 17:6-7 reminds us, that is what followers of Jesus are all about, after all.

With Covid-19, I think that God is urging us to learn from the experience and press the reset button. How we respond to this present disruption is the important thing. The world is indeed being turned upside down and inside out. Not only are we seeing widespread disorientation and suffering, but the crisis is also exposing the failings of an economic and political system that has exploited and dehumanised for far too long.

The books of the old and new testaments give us a powerful insight into how we could and should respond to current events, helping us to see beyond the pain and tragedy and recognise how we can reform and renew our lives and our world.

As the Covid-19 pandemic has unfolded it has brought to mind an interview I did many moons ago with Dame Alix Meynell, one of the most notable public servants of the 1940s and 1950s. ‘You see’, she said ‘the war changed everything. Ideas and policies that were regarded as wholly unacceptable, became acceptable, if not inevitable’. Her point was that the experience of the war had brought about a new way of thinking, a new economic ‘consensus’ that is often associated with the so-called ‘Keynesian revolution’. As we reflect on the sheer war-time scale of the changes that the Covid-19 crisis has brought in its wake, the implications of Dame Alix’s recollections strike me as having an urgent relevance for today.

Today we face a war against an enemy within, rather than from without, but it seems to be having a transformative effect on both economic policy as in the 1940s, but also a remarkable impact on our social life. It appears that, just as World War Two changed everything, the ‘war’ or ‘battle’ against Covid-19 is also changing everything.

We are truly living through a great disruption as our deserted streets seem to mirror our wilderness within. It is curious for me because this Lent I decided to take Rabbi Jonathan Sacks’ The Book of Numbers: the Wilderness Years with me on my journey through Lent. (Last year it was Dante’s The Divine Comedy).

As the crisis unfolded, and as my part of Wales was turning slowly into a desert, it brought home that human beings need a wilderness experience. We need to be open to divine disruption. In the wilderness, Israel learned many things. Above all, what we can learn from their 40 years in the wilderness is that it is not easy being free. The Lord had set the people of Israel free from slavery, but it took quite a while for them to learn how to be free. It seems to me that Lent is a period in which we learn how to be free and what true freedom means.

This Lent has been the closest I have got to living in a wilderness. And yet, I look around, and to my amazement I see the deserted streets flowering with examples of kindness and solidarity, and a sense of the common good seems to be growing. Now, more than ever, I see and hear sights and sounds of what real freedom looks and sounds like.

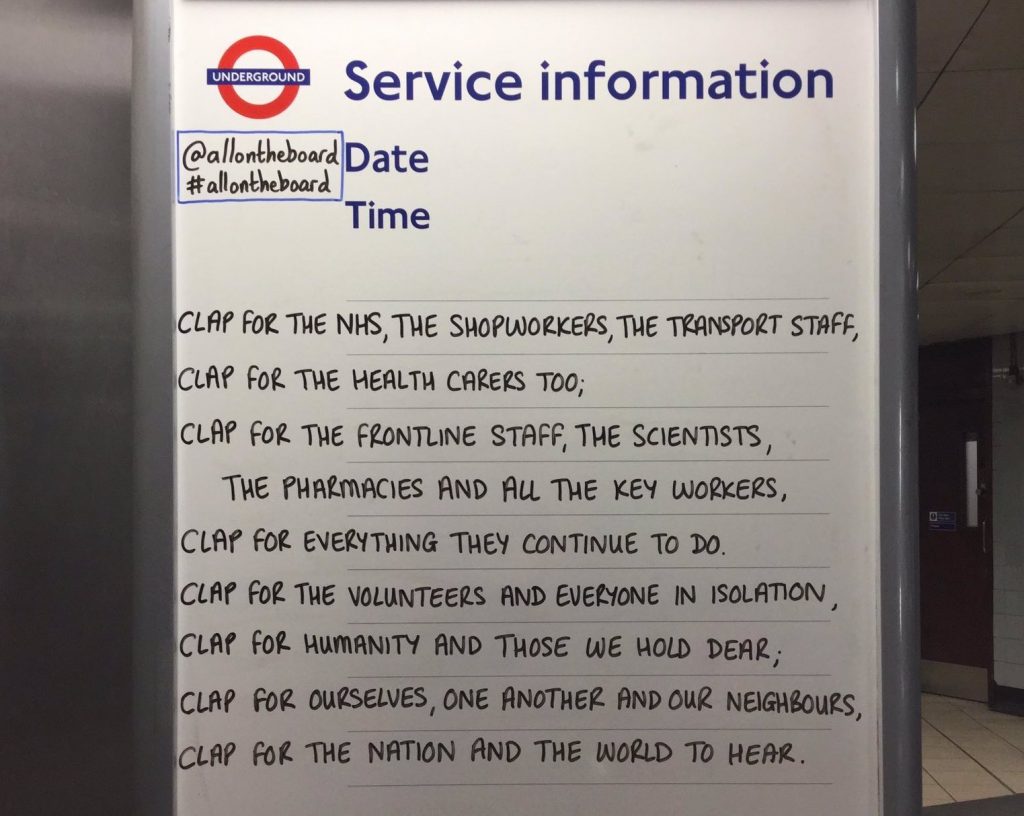

I see and hear real freedom on Thursday evenings when people come out into the streets of my town clapping and banging pots and pans to say ‘thank you’ for people who work in our NHS and in other services. This is the kind of freedom that is captured in common good thinking. Perhaps, we needed to have a great disruption, an experience of the wilderness for us to grasp the truths which this thinking contains.

Long ago the moral and ethical dimensions of economic theory and practice were excised from mainstream political economy, regarded as largely irrelevant to policy making. And as I have confessed elsewhere (in On the Road to the Common Good) I was not alone in supporting that view. However in recent years I began to see the moral limitations of ‘Keynesianism’ and I changed my mind. I came to see that moral and ethical principles are fundamental for good policy making.

But, and it was a big but, I just could not see how the powerful ideas that Together for the Common Good and others have promoted could actually change anything. The world would have to be turned upside down. But how? Like Dame Alix who saw a ‘revolution’ at first hand in a war-time government, I think we are now seeing how the moral aspects of public policy are coming to the fore.

As we consider the Covid-19 crisis and its aftermath, we realise that the re-build required will need to be underpinned by a consensus, where human beings understand the relationship between virtue and social, political and economic life.

The crisis is showing us in stark terms that it is only when we think of others and love our neighbours, when we show solidarity with those who need our help, and when we work together to build the common good, that we flourish as human beings.

The complexity of our problems requires far more than the application of state power or the interplay of market forces or technological gadgets. Ultimately real human progress is moral progress. This is what Aristotle and Aquinas argued, and it is revealed in the experience of Israel in the wilderness. Our dominant culture of liberalism is so very deficient in understanding this.

The story of wilderness and sacrifice told in the book of Numbers is absolutely necessary to our realising the possibilities of freedom. Democracy, as a way of life, is dependent on virtuous citizens who understand the importance of the common good to building a just society.

Perhaps, just perhaps, this great disruption, despite the human suffering, will provide the impetus for the emergence of a new kind of political and policy agenda: a new political settlement for the common good. This is, after all, what the ‘post-liberal’ movement has been calling for for more than a decade. Now, it is just possible that it might actually happen.

Our deserted streets this Lent have forced us to confront a most uncomfortable truth. We share in a common humanity and for our survival we must work together for the common good. We like to think that because of our wealth or intelligence that we can live without recognising how we are deeply and profoundly interconnected and dependent on one another. A prince may catch the virus from a pauper. The pauper may get it from a prince. The person who lives hundreds of miles away is really a next door neighbour. This is no mere metaphor but a description of a reality. As the world is turned upside down, we have to seize the opportunity to transform our life together.

When we take this reality to heart then the principles embodied in common good thinking are no longer an irrelevance to the theory and practice of public policy, but reveal great truths about what it means be a human being, and we neglect these truths at our peril.

When we focus on the common good we see a new way of understanding the problems facing humanity which cuts across the divisions of faith and party politics. We urgently need that new politics and a new consensus. Perhaps, just perhaps, in the wilderness of 2020, that new settlement may flower and set seed.

© D.W. Parsons

Professor Wayne Parsons was formerly professor of public policy at Queen Mary, University of London. He now works as a consultant and independent scholar.