Better Together

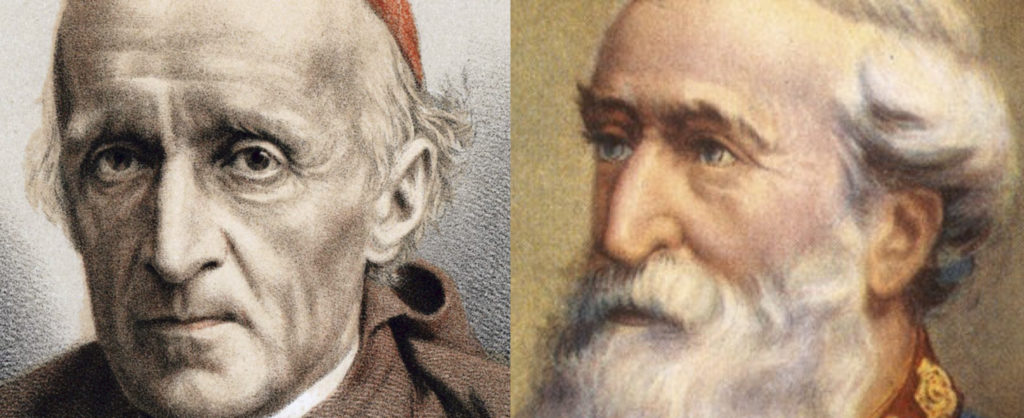

The collaboration between Cardinal Manning and William Booth at the end of the nineteenth century is a fine example of churches working together to defend the interests of communities in the industrial age. Here, William Kent learns how their relationship developed.

The story of the Manning-Booth friendship

A few years ago, whilst going through the papers of the late Cardinal Manning (1808-1892), I came across two handwritten letters from the founder of the Salvation Army, William Booth (1829-92). While the original copies of Manning’s letters to Booth were not in the collection, I did later manage to find extracts of these printed in some secondary literature. It was a great privilege to discover this material for it sheds a fascinating light on the relationship between these two renowned Victorian Churchmen and their shared concern for the poor of England.

In 1890 William Booth published his famous book “In Darkness England”, a response to the social ills of the day. He forwarded this text on to the Catholic Archbishop of Westminster, requesting his feedback, as well as stating:

“I feel the difficulty of the subject and even after all the attention I have been able to give to the theme, and the information I have obtained from what appear to be the very best sources, the problem is so colossal that I humble at my own audacity in attempting to deal with it”.

Manning, who deeply shared the social concerns of Booth, replied favourably, saying

“you have gone down into the depths. Every living soul cost the Most Precious Blood, and we ought to save it, even the worthless and the worst. After the Trafalgar miseries I wrote a “Pleading for the Worthless”, which probably you never saw. It would show you how completely my heart is in your book”.

Booth had seen Manning’s article and replied:

“I did see your “Pleading for the Worthless”, and appreciated it. Something must be done and that immediately. The winter is upon us, and we shall have the hungry multitudes clamouring for the promised help, and have nothing ready for them. You cannot reason with starvation. Arguments are thrown away upon despair”.

Yet a shared vision of service of the poor were not all that united the two Churchmen, they also had a deeply personal connection. In 1890 William Booth lost his wife Catherine to cancer. He movingly described his feelings to Cardinal Manning, stating

“I am quite sure that your Eminence heartily sympathises with me in the heavy loss I have been recently called to suffer. Although we had watched and waited for death for many months … still the blow was very sudden when it did fall. We feel it very seriously. My loss is immeasurable [in] almost every way. But He is able to make His consolations abound.”

Manning had been an Anglican priest and had himself been married. He too had felt the pain of loss when his young wife Caroline had died. It is clear that Booth received consoling words from Manning for he wrote again, saying

“Thank you very much for the kind words you have sent me. I feel they came from your heart – I assure you they have gone to mine”.

I have to date not found any further correspondence between these two great figures of the nineteenth Century. Yet even in this brief exchange there is much to reflect on and much to inspire us today. Manning and Booth both shared a vision of human dignity rooted in the Gospel and they both worked tirelessly for the Common Good in Victorian society.

Concerns about the new issues facing European society during the social transformation of the late-nineteenth century were shared by other contemporaries of Manning and Booth. In 1891, Pope Leo XIII published the first of a series of letters (encyclicals) on ethical issues. Rerum Novarum (Of New Things) addressing the new issues facing European society as a result of the Industrial Revolution and the social transformation this brought about. Through Rerum Novarum, the tradition of Catholic Social Teaching that inspires T4CG was born.

In Manning and Booth we find an inspirational example of two ‘brothers in Christ’, individuals rooted in different traditions reaching out across a gulf and working together in a shared mission of love. As with contemporary Christian friendships, collaboration need not mean sinking differences. Both Manning and Booth were strong in their convictions – each had a robust identity, yet they testify movingly to the power of cooperation despite difference.

William’s son, Bramwell Booth, who was to take over the Salvation Army, summarised this powerfully, stating:

“the Salvation Army was not within [Manning’s] Church, but it was at least within the protection of his Church’s prayers. He joined heartily in several attempts to raise funds for us. He saw the worth of those whom society esteemed as worthless, and he liked The Army because it saw the same thing, and said so, and went to work to help them.”

William Kent

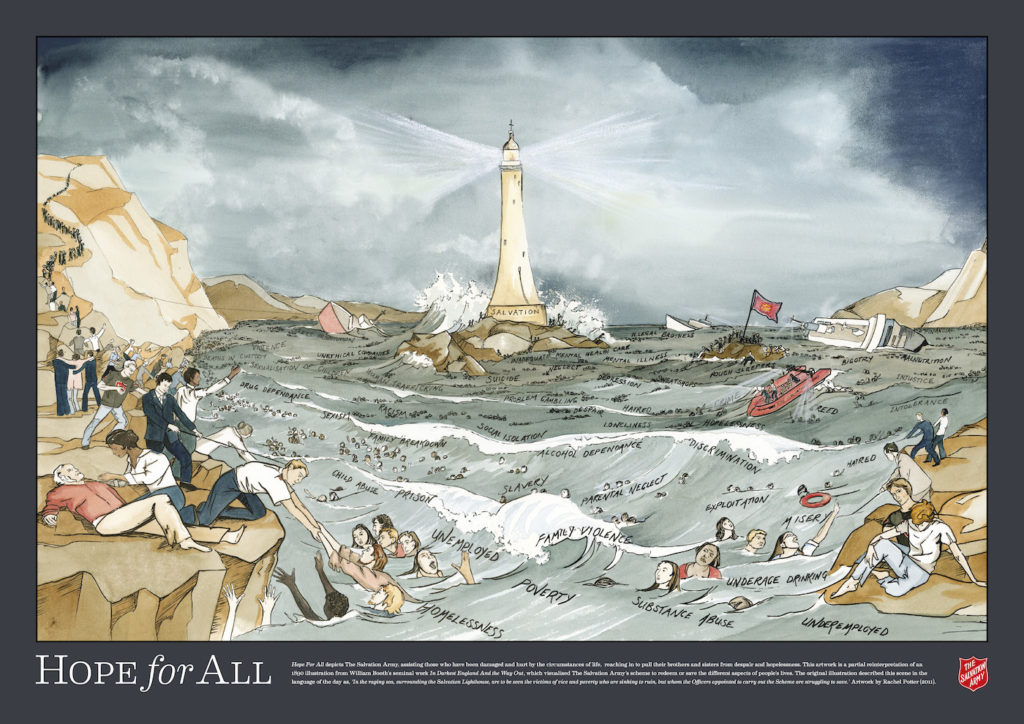

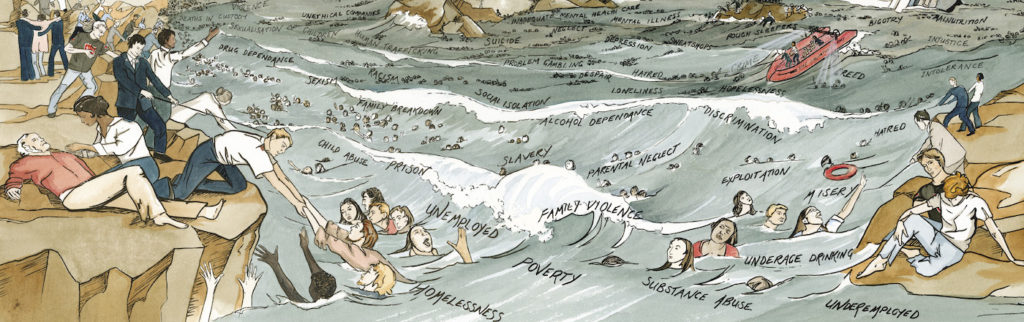

The header image below is a partial reinterpretation of a portion of an illustration from The Salvation Army’s seminal work In Darkest England And the Way Out, co-authored in 1890 by Catherine and William Booth and W. T. Stead, which visualised The Salvation Army’s scheme to ‘redeem’ or save the different aspects of people’s lives. The 1890 illustration was described as follows, in the language of the day: ‘In the raging sea, surrounding the Salvation Lighthouse, are to be seen the victims of vice and poverty who are sinking to ruin, but whom the Officers appointed to carry out the Scheme are struggling to save.’ Contemporary artwork by Rachel Potter. Shared by kind permission from the Salvation Army.

Stay Connected

Explore more content like this by subscribing to Together for the Common Good on Substack.

You may also be interested to read To Live A Decent Life by Jenny Sinclair