Together for the Common Good is a non partisan Christian charity dedicated to civic and spiritual renewal. Inspired and informed by Catholic Social Teaching, a tradition that is at once both socially conservative and economically radical, T4CG is always looking for practical examples that show how this approach can guide good statecraft that puts families and communities first. On the whole, the political class has lacked the courage to grasp the vision of a common good politics, but there are some notable exceptions.

Here, writing in 2015, Frank Field critiques his own party for disengaging from its core values, predicting election losses which later materialised. He goes on to propose constructive steps to renewal, making proposals that resonate strongly with Christian principles. He describes practical actions relating to family, work, the welfare system, migration, democracy and more. Frank was an experienced politician and independent thinker who loved his country, its decency and uniqueness. His legacy is poignant today, as we face a vacuum where serious political imagination ought to be.

A Blue Labour Vision of the Common Good

1. Introduction

Labour’s leadership may not have thought through the challenge Blue Labour poses. But it can be easily stated. Blue Labour confronts the cultural war successive Labour leaderships have waged against the moral economy of Labour’s core working class voters. Blue Labour therefore poses the most fundamental of challenges to the Blairite electoral strategy that, despite changes in personnel, remains in place. Had the leadership given serious thought to Blue Labour its worry, if not annoyance, would have quickly turned to alarm. For if Blue Labour prevails it will herald a new centre-left electoral strategy based on a different meaning of the term progressive and how this progressiveness will be enshrined in policies promoting the common good. Alternatively, if the Blairite electoral strategy is maintained, and past trends are in any way a guide to the future, Labour’s core vote will continue to disengage. But from now on there is likely to be a second sting in the tail of departing Labour voters. Instead of joining the great army of non-voters, the march of Blue Labour voters may turn directly to UKIP who offer an alternative vision of the common good that is more akin to their own.

2. The writing on the wall

British post-war politics are often discussed in terms of the electorate’s disengagement from the two major parties. This is true, but it is only part of what I would contend is a more much more serious long-term threat to the stability of our democracy. A number of voting patterns are detailed in the table below. I have taken 1950 as a starting point for this analysis as the 1945 election was fought in wartime conditions with millions of voters displaced at home and millions more in the services overseas.

Table 1: Number of votes cast in General Elections since 1950

| Votes (millions) | ||||||||

| Con2 | Lab | Lib3 | PC/SNP | Other | Total Votes | Electorate | Non-voters | |

| 1950 | 12.47 | 13.27 | 2.62 | 0.03 | 0.39 | 28.77 | 34.41 | 5.64 |

| 1951 | 13.72 | 13.95 | 0.73 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 28.60 | 34.05 | 5.45 |

| 1955 | 13.29 | 12.41 | 0.72 | 0.06 | 0.29 | 26.76 | 34.85 | 8.09 |

| 1959 | 13.75 | 12.22 | 1.64 | 0.10 | 0.16 | 27.86 | 35.40 | 7.53 |

| 1964 | 11.98 | 12.21 | 3.10 | 0.13 | 0.24 | 27.66 | 35.89 | 8.24 |

| 1966 | 11.42 | 13.07 | 2.33 | 0.19 | 0.26 | 27.26 | 35.96 | 8.69 |

| 1970 | 13.15 | 12.18 | 2.12 | 0.48 | 0.42 | 28.34 | 39.34 | 11.00 |

| Feb 1974 | 11.83 | 11.65 | 6.06 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 31.34 | 38.73 | 7.39 |

| Oct 1974 | 10.43 | 11.46 | 5.35 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 29.19 | 40.07 | 10.88 |

| 1979 | 13.70 | 11.51 | 4.31 | 0.64 | 1.07 | 31.22 | 40.07 | 8.85 |

| 1983 | 13.01 | 8.46 | 7.78 | 0.46 | 0.96 | 30.67 | 42.19 | 11.52 |

| 1987 | 13.74 | 10.03 | 7.34 | 0.54 | 0.88 | 32.53 | 43.18 | 10.65 |

| 1992 | 14.09 | 11.56 | 6.00 | 0.78 | 1.18 | 33.61 | 43.28 | 9.66 |

| 1997 | 9.60 | 13.52 | 5.24 | 0.78 | 2.14 | 31.29 | 43.85 | 12.56 |

| 2001 | 8.34 | 10.72 | 4.81 | 0.46 | 2.03 | 26.37 | 44.40 | 18.04 |

| 2005 | 8.78 | 9.55 | 5.99 | 0.59 | 2.24 | 27.15 | 44.25 | 17.10 |

| 2010 | 10.70 | 8.61 | 6.84 | 0.66 | 2.88 | 29.69 | 45.60 | 15.91 |

| 1. For elections up to 1992, the Speaker of the House of Commons is listed under the party he represented before his appointment. From 1997 the Speaker is listed under ‘Other’. | ||||||||

| 2. Includes Coalition Conservative for 1918; National, National Liberal and National Labour candidates for 1931-1935; National and National Liberal candidates for 1945; National Liberal & Conservative candidates 1945-1970. | ||||||||

| 3. Includes Coalition Liberal Party for 1918; National Liberal for 1922; and Independent Liberal for 1931. Figures show Liberal/SDP Alliance vote for 1983-1987 and Liberal Democrat vote from 1992 onwards. | ||||||||

Four major trends can be discerned from these post-1950 voting figures. The first centres on the Conservative vote. Up until 1997 Conservative votes fluctuated between 12.5 and 14 million – with a total vote well above the 13 million in five post-war general elections. This level of support collapsed in 1997, reaching its lowest point of 8.3 million votes cast for Conservative candidates in the following 2001 election. In the past two elections the Conservative vote has risen by 2.4 million.

Second, in terms of numbers of votes cast, the Labour Party has never registered greater support in the votes cast for it than it gained in 1951. The 1997 election recorded 13.5 million Labour supporters, but this was still nearly half a million below the 1951 high point and during this period the number of voters increased by 9.8 million. Since 1997 Labour support has fallen by 5 million votes – and I promise you that it is not a misprint. There has been a fall of 5 million votes in the space of three general elections. And this was at a time of a further rise in the numbers of voters – by an additional 1.8 million. As voters disengage in significant numbers from the two major parties, the size of the electorate has been rising. Since 1950 the electorate has risen by over 11 million. The total vote since that election going to the two main parties has fallen from its peak by over 8.5 million at a time when the electorate has risen by nearly a third.

A beneficiary of this disengagement from the two major parties was the Liberal Democrats. Liberal Democrats support has grown from 2.6 million votes in 1950 to 6.8 million votes at the last election. Here is the third movement in party support which can be gleaned from the table. This trend is unlikely to hold in the next election, and is anyway not as spectacular as the fourth trend. The total of non-voters who have nearly tripled from 5.6 million in 1950 to 15.9 million in 2010 – a greater number than the total votes cast for all Labour and Liberal Democrat candidates. It is true that this total is down from the peak of 18 million in 2001, but this fall looks as though it has overwhelmingly benefited the Conservative Party whose vote increased more than the decline in the number of non-voters.

3. The Not So Strange Death of Labour’s Skilled Working Class Vote

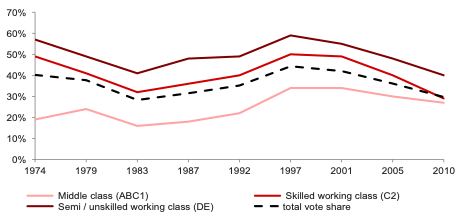

Of course this trend may peter out. Looking at the table the ebbs and flows in party support are clear. So this increase in the Tory vote may not be maintained. Indeed, it might be reversed. But my concern with Tory Party fortunes is limited to how they might impact upon Labour Party support. Again, this horrendous decline in Labour support over the last three elections may be reversed. But I want to suggest that it won’t be unless one looks, first, at which groups have been disengaging fastest and then, at Labour policies that might attract them back. Here we need to disaggregate the Labour vote by social class, and then, secondly, consider which policies around the theme of the common good might reverse those trends. The breakdown of the changing level of class support for Labour candidates since the election of 1974 is given in the graph below.

Graph 1. Proportion that voted for Labour in General Elections by social class, 1974-2010

Source: These data from MORI/Ipsos MORI election aggregates 1979-2010. 1974 figures taken from a Louis Harris poll. The Data underlying this chart is available on the IPSOS-Mori website: http://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/poll.aspx

What do the trends in the graph tell us about the collapse in Labour support? Three important trends are at work. The overall decline in the semi and unskilled working class Labour vote has been in line with overall decline in the party’s vote. The poorest in the electorate have been deserting candidates in line with Labour’s overall decline. So much then for being ‘the party of welfare’, as the Tories like to dub us. Yet, this false link which is all too firmly made now by large numbers of voters has not resulted in an electoral reward from the very group that gains most from the welfare state.

The group of the electorate most likely to see Labour as the party of welfare is the skilled working class, and as we can see from the graph it is this group that is punishing Labour most trenchantly. The decline in Labour’s support amongst the skilled working class electorate is shown to be greater than the decline in Labour’s overall vote, particularly from the 2001 election onwards. Between 2005 and 2010 Labour’s proportional share of the skilled working class vote is less than its overall share in the total vote.

Finally, the third trend apparent in the table is that while Labour’s share of the middle class vote has declined, it has done so much more slowly than the overall decline in the party’s vote, and particularly its vote from the skilled working class. This is the group least disaffected by Labour’s vision.

4. Politically Homeless Labour Voters

Where is this core vote going? Again the answer appears disarmingly simple and is given in table 1. For most of the period an ever-greater proportion of Labour’s core voters has become politically homeless with the vast majority of departing voters appearing not to vote at all. Hence the decline in turnout which I have commented on as one of the most significant trends in recent British politics.

Once voters are on the move this process seems to gain its own momentum. Party bonds are rarely cast asunder by a single event. The breaking of loyal bonds often begins imperceptibility. When R. H. Tawney was shot and left for dead in one of the all too numerous shell holes that pockmarked the Western front, he realised, indiscernibly at first, his roots in life were being loosened and that, later, he would never feel quite the same about death. So too with the transference of political loyalty. Once friends who were keen supporters start expressing their doubts it becomes easier to express one’s own doubts and doubts can all too often lead to disengagement.

A movement from party loyalty to the status of being politically homeless, where no vote is cast, is dangerous enough for a party’s future wellbeing. But homelessness does not necessarily define a permanent state of being. It is from this homeless group that an even greater danger is now being posed to Labour. A number of these voters are calling a halt to their homelessness, or their non-voting status, and are deciding to move to another party. A significant proportion of the homeless amongst ex-Labour supporters is now voting UKIP. At the European election a fifth of the UKIP vote was from those who had previously stopped voting. And a significant part of those Labour voters alienated by New Labour is choosing UKIP. Here they see a home in which their values are displayed on every wall, if not by the wallpaper itself.

The economic pull that Labour exerts remains. Working class Labour voters believe that they would be better off financially under Labour. And while the views of this group on Labour’s economic competence are important, the party now finds that the cultural push away from Labour is so strong that the economic pull is negated for a significant and what looks likely to be a growing proportion of this group of the electorate. A sizable part of ex-Labour voters have been repelled by the policies promoted by a largely non-working class party elite with whom these ex-voters find it difficult to sympathise and vice versa.

5. Values Trump Money

These trends challenge the now conventional wisdom on which New Labour’s electoral strategy was based. The decline in the overall Labour vote in the period from 1966 was to be counted, reasonably enough, by reaching those parts of the electorates that had turned their face against the party. In doing so, it was assumed, dangerous as it turned out, that this process of wooing middle class voters could be pursued and the needs and responses of Labour’s core voters ignored. The view that these voters had nowhere else to go was the comforting phrase chanted by Labour’s chattering classes. But as we have seen Labour voters have a mind and determination of their own as increasing number of them move. So why the move?

Let me reinforce the view I hinted at in the opening paragraph. This decline in Labour’s vote has not been driven by economic alienation, although that clearly has played a part. A more fundamental force has been at work. This force is primarily cultural and ethical, not economic.

A significant proportion of deserting Labour voters, and a significant proportion of working class voters who remain loyal to the extent that they continue to vote for Labour candidates, are hostile to the kind of society they perceive Labour is now in business to promote. They do not see Labour as being committed to the flag – i.e. being proud of the country, or having a clear stand in defending the country’s borders – i.e. soft on immigration, or in promoting a welfare state where rewards have to be earned – i.e. catering largely for the freewheelers, rather than hard working families.

They witness a Labour Party that all too often stands for a distribution of public services that they find repulsive; a housing allocation system that favours the new comer and the social misfit over good behaviour over decades. They see Labour as soft on vulgar and uncivilised behaviour that plagues their lives and from which the rich shield themselves. Moreover, they witness a leadership that never expresses the anger they feel as the world they stand for is mocked and denigrated by hoodlums for whom official Labour always seems to have an understanding word.

Hence the disengagement from a Labour vision that repels working class voters who once saw, or who wish to see, decency as the cornerstone of Labour’s Jerusalem. This movement from voting Labour to non-voting, and then to another party, stands on its head the Marxist assumption that has unquestioningly underpinned Labour’s electoral strategy. It is values, not economic interests, which are now determining party loyalty for a significant proportion of Labour and ex-Labour voters. In the period up to the 1960s Labour’s economically based social strategy reflected the moral economy that governed a very large part of working class family life. That is no longer so and it is working class social values, rather than economic interest, that now take an increasing hold of working class voting loyalty. Four values predominated this vision of the common good.

A pride and love of one’s country and a near blind loyalty in taking its side against whatever is thrown against it.

A loyalty to old friends, particularly those have always been prepared to fight on one side, rather than occupy the opposing trenches.

A central belief that duties beget rights and that privileges have to be earned.

An emphasis on making contributions as a means to earning entitlements and that it is in joining in, so to speak, by making contributions that defines society’s borders, both socially and geographically.

Late in the day the Labour leadership has begun to wake up to the threat its values based programme poses. But the fundamental significance of this challenge remains misunderstood and undervalued. Not surprisingly therefore the party’s response has been inadequate. So what policies are necessary to demonstrate to foot loose and would be foot loose Labour voters that their values will regain their old primacy in whatever coalition of voters Labour attempts to put together? I would suggest four initiatives are fundamental to underpin and appeal to that new coalition of voters, built around Blue Labour’s conceptions of the common good. Each of these approaches encapsulates an idea of the common good in everyday politics.

First, the threat the current scale of immigration poses to our national identity has yet to be met. There is no way the clock can or should be turned back. But without a fundamental control of the borders there is nothing to prevent another seven million immigrants coming into Britain during the next decade and a half, to match the seven million who have entered the country since 1997.

Here the style of Labour’s fight back is crucial. The party has recently tried to respond to the concerns of the whole country on the issue of immigration, and particularly those of its core voters, by listing a number of detailed and worthwhile reforms. But the reforms are out of time. Had they been proposed in 1997, they might have been seen by the electorate as a robust response. Not so now. The politics of regaining Labour’s core vote entails the use of initiatives which speak sacramentally to voters. The party’s outward policy announcements have to be seen to reflect an inward change in the attitudes and beliefs of the Labour leadership. How might this be achieved?

Labour needs to commit itself to the end of the free movement of labour within the EU. No one will underestimate the size of this task. And for those who caution this objective as unachievable, and that the leadership should not embark upon it, seem to ignore totally the impact such a stance would have on the attitude of Labour’s lost voters. The party’s core voters will mark Labour’s card as trying to defend their interest instead of standing idly by and witnessing yet further erosions of their living standards, and particularly so when the leadership wants to fit the election on the decline in living standards. Battles might be lost, but the core voters will mark Labour’s card trying to promote their idea of the good society. The aim, of course, should be to win such major battles.

Second, the primary role of the family has to be reasserted through policy commitments and not simply by words. Core voters accept the diversity of family life. But the traditional model remains for most working class Labour voters the ideal to aim for, and through which their happiness is maximised. It is not only that within this framework that most children are best nurtured. Working class women, in particular, stress the importance to their happiness of having a partner in full time work so that their work can be fitted around the needs of their family. For it is within this social and communal world that working-class women, and now an increasing number of middle class women, say their greatest happiness is found. This fundamental realignment of Labour’s policy is not a disguised plea to begin discriminating against other types of families and households. It is, rather, to cease discriminating against the traditional family, and particularly so through the welfare state.

There are also powerful fiscal and social reasons for a recommitment to the traditional family. Child poverty is a major problem in modern day Britain yet there are almost no, repeat, no, poor children in households where one partner works full time and one part time. ‘If you do not want your children to be poor, you need a partner who works’ should be part of our social highway code.

Third, the working class belief that it is the performance of duties which gives rise to rights has to be enshrined in our welfare state. The leadership’s welcome phrase of ‘something for something’ has to be taken from sound bite and be enshrined in actual policies.

The galloping spread since 1979 under both Tory and Labour government of means tested assistance in the form of social security, tax credits and housing and council tax benefits, have to be seen for what they are. They amount to a full frontal attack on a working class moral economy that believes in work, effort, savings and honesty, and that these great drivers of human endeavour should be rewarded rather than penalised. The welfare state has to be reconstructed away from means testing onto a National Insurance basis. Such a revolution cannot be achieved over night. But the first steps in a clearly marked 20-year route map have to be taken, and a commitment to that route map given.

Any benefits system does more than begin to rebuild support for a welfare state. It also defines acceptable behaviour, membership of a community and also, not least importantly, begins again to draw the lines around national identity. National borders can be enforced not only by geographical boundaries and border agencies but by welfare as well.

Fourth, work is crucial to human dignity, the well-functioning of the family as well as the prosperity of the nation. Labour must commit itself to a full employment strategy with higher paying jobs being central to this objective. Part of those jobs will be created by a commitment to build by the end of the Parliament 300,000 social houses each year – the Tory commitment in 1951. A building programme of housing would also be one that strengthens families. It is difficult to survive, let alone thrive, in the semi-slum conditions into which all too many families are now condemned.

But, likewise, running an exchange rate policy will be significant to achieving this employment objective. Exchange rates do not only help to determine the level of exports. It is also crucial for building an effective import substitution strategy. An effective exchange rate policy must also be concerned with preventing imports, including food, basic materials, as well as manufacturing. Being obsessed by the level of exports is important, but is only part of the story. Employment levels are directly affected by both the level of exports and also imports.

6. The Forward March of Blue Labour

A Blue Labour strategy is not one simply about shoring up Labour’s core voters. It is certainly that. But it is also a strategy on which elections can be won. The moral economy to which Blue Labour voters attach such importance is one which has a universal appeal. Why do I say this?

Public and private ethics in this country are the product of a Christian inheritance. While during the 19th century the country slowly took leave of Christian dogma it ensured that much of Christian teaching was secularised. The agent of this successful secularisation was the growth, and then for a period, the dominance of English idealism to which most party leaders subscribed, as did their followers.

This left us with a common ethical code onto which party divisions were imposed. The decency therefore that has driven so much of Labour’s vision of both private and public common good is one shared by the members of other classes. The appeal to country, loyalty to old friends, that duties beget rights, are all sentiments that appeal across classes. It is on this universalism of Blue Labour’s common good that Labour should begin rebuilding that wider coalition of voters which is so crucial to general election successes.

Frank Field

Frank Field CH, PC, DL was MP for Birkenhead for 40 years, from 1979 to 2019. He served as a Labour MP until 2018 and thereafter as an independent. One of the most famous backbenchers in the House of Commons, he campaigned continually and fearlessly for intelligent ways of ensuring the welfare of the poor. Field served briefly as Minister of Welfare Reform in Tony Blair’s first government, from 1997 to 1998. Field resigned following differences with Blair, and as a backbencher, soon became one of the “New Labour” government’s most vocal critics. In 2018, Field resigned the Labour whip citing antisemitism in the party, as well as a “culture of intolerance, nastiness and intimidation” including in his own constituency. In 2020 he was awarded a life peerage and then as Baron Field of Birkenhead served in the House of Lords as a crossbencher until his death from cancer in 2024.

A man of integrity, a dear friend, and one of our country’s finest common good thinkers. May his name be blessed. Frank Ernest Field: 16 July 1942 – 23 April 2024.

This essay is shared here in memory of Frank’s immense contribution to British political life. It was first published in 2015 as chapter 3 in Blue Labour: Forging a New Politics and is shared here with the kind permission of co-editors Ian Geary and Adrian Pabst. We are grateful also to share this with the blessing of Andrew Forsey, who was head of Frank Field’s office in the House of Commons between 2013 and 2019 and who has been National Director of Feeding Britain since 2019.

You may also be interested in The Economics of the Common Good by Maurice Glasman, founder of Blue Labour, and this interview where he talks about his book, Blue Labour: the Politics of the Common Good.

This article was featured in T4CG’s Pentecost 2024 Newsletter. Subscribe to the T4CG newsletter here

Together for the Common Good is totally dependent on the generosity of people like you. If you enjoyed this article, please consider making a donation to support the work. Anything you can give, no matter how small, will make a difference. Click here to donate now