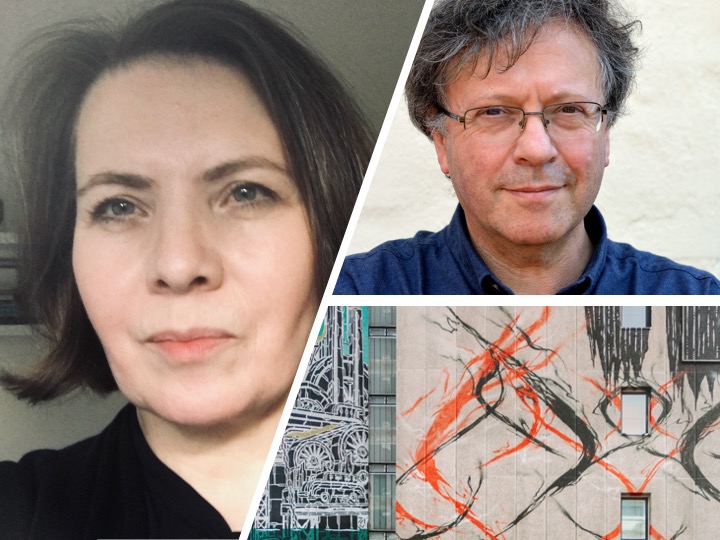

Here we share a discussion between Jenny Sinclair, Founder and Director of Together for the Common Good, and Steve Wyler, co-founder of A Better Way, about whether the concept of covenant could help us achieve a collaborative society.

Steve: Let’s start off by understanding what we are up against. What do you see as the underlying difficulties we face, across society?

Jenny: Put simply, we have allowed a contract culture to infect our way of living. The story of the modern West is about a society built around transactional exchanges, managed by contract, determined by globalized economics.

The results are increasingly clear – the evisceration of civic life, the thinning out of local forms of a common life that would enable communities to work out their challenges with one another, and social isolation, even between people who live in the same neighbourhood.

Under a contract culture, inequality has grown, people have become atomised, made into consumers, service providers and service recipients. Contract is an expression of an individualistic society, it is based on mistrust of others, and this has allowed the dominance of human beings by money power and state power. Relationships between us have been weakened. This is why we see nihilistic symptoms like rising loneliness, depression, suicide and so on.

This is a modern phenomenon, a direct result of neoliberalism. It is accelerating under Covid -19. It is not the way we are designed to live. It doesn’t have to be this way. It is a failed story and we can replace it with a new story.

Steve: So what is the new story?

Jenny: The foundations for the new story can be found in a deep and ancient concept which has informed and nourished ideas about society for centuries: the concept of a ‘covenant’.

Steve: Can you explain for me what you mean by a covenant?

Jenny: A covenant is a reciprocal relationship between people. And critically, a relationship which is based on trust, not on financial transaction or legal instruments, one which is durable and lasting, unlike a contract which is time-limited.

A covenant is based on the recognition that we are social beings and that social beings thrive in relationships. And that good relationships require our individual uniqueness and our freely given agency.

Covenant is a verb as well as a noun – in a marriage we covenant ourselves to each other. We can understand how covenant works when we think of a healthy family in which people of different generations are covenanted to each other, belonging to each other without limit of time and within unconditional love.

The etymology of covenant is connected with the idea of oath in Latin – sacramentum – or promise. A covenant can be broken when we fail in our obligations to each other. As human beings we have a tendency to break our promises, to let each other down. We fail repeatedly, that’s what we’re like. Therefore covenant also requires forgiveness and redemption, constantly allowing a path back.

Steve: These are powerful ideas. They certainly resonate with many aspects of Better Way thinking. After all, one of our principles is that ‘relationships are better than transactions’. And we say that ‘deep value is generated through relationships between people and the commitments people make to each other’.

But I am struggling a little with the term ‘covenant’. Isn’t this a religious term, and doesn’t it imply the presence of a God, for a covenant to be meaningful?

Jenny: No, I don’t think so. The term does come from ancient scripture, which by the way is packed with stories of how people overcame adversity. But understanding the meaning of the concept does not require religious belief. There is a wisdom here that is free for all to draw on.

Most people can accept that it is a reality of existence that there is something bigger than oneself as an atomised individual. Whether or not they believe in God, they can experience a sense of humility and interdependence that comes from the recognition of our relationship with nature and with each other as fellow human beings.

So this is a concept that can be meaningful across faith and secular interests. And it’s a rich concept. The more you engage, the richer it gets.

Steve: So, I think you are saying that we need to move from a contract paradigm to a covenant paradigm. How do we make that happen?

Jenny: We need to build a new narrative. Our language is dominated by contractual thinking, both as applied to the market ( ‘products’, ‘clients’, ‘competition’, ‘capital’, etc.) and the state ( ‘services’, ‘users’, ‘problems’, ‘planning’). The language of covenant is very different (‘trust’, ‘neighbour’, ‘vocation’, ‘belonging’, ‘dignity’, for example).

Steve: I can see that language is important, and that we need to become more aware of the implications of the language we use, and how it can reinforce a prevailing way of seeing the world, if we want to change the paradigm. But what other types of action are needed?

Jenny: Covenant implies a commitment to place. By covenanting with neighbours and local institutions where we live we can start to generate a renewed civic life. We can recognise that each local institution (clubs, associations, charities, and other local bodies) has a unique civic role alongside others. Everyone has a part to play here.

Steve: What about at a wider systems level?

Jenny: The wider task is to build a common good between different interests and groups in society (e.g. unions and business, faith and secular, old and young). And this includes working across political divides, building alliances across class, across race.

But to do this we need to cultivate a culture of listening, not promoting an agenda. This means getting to know our neighbours in one-to-one conversations. Building genuine relationships of mutual encounter, not instrumentalising each other for a campaign.

Steve: And our national institutions. Do they need to change as well?

Jenny: Yes. Our institutions need to be formed and judged on the basis of covenant rather than on contract or economics. They need to be durable and faithful across generations. Historically, we can see that in their origin and intention, trusts and endowments, the common law, Parliament and our liberties do in fact come from this covenantal understanding. We need to rediscover this.

Steve: This is beginning to feel like a profound and radical change.

Jenny: It is. And subversive in the best sense. We need to become ‘difficult to manage’. Our relationships will strengthen us against being instrumentalised by the market and by the state. Relational power is an insurgency against money power and state power.

Steve: An insurgency – that’s quite something.

Jenny: Yes, but there is of course a risk that ‘covenant’ will become just another government buzzword and the latest casualty in the stream of meaningless words. This has happened many times before but it shouldn’t put us off.

We should use the language with care, and only use it when what we are actually doing reflects the truth of its meaning. Certainly not to chase after the latest government funding. This is a matter of conscience.

Steve: Thank you Jenny, this has been a very rich conversation, and one which I am sure we will take forward in the Better Way network.

This first appeared via our friends at A Better Way Network in November 2020.

Like what you are reading? More inspirational content from Jenny Sinclair can be found here: https://togetherforthecommongood.co.uk/news-views/from-jenny-sinclair