Communicating the Good:

The Politics and Ethics of ‘The Common Good’

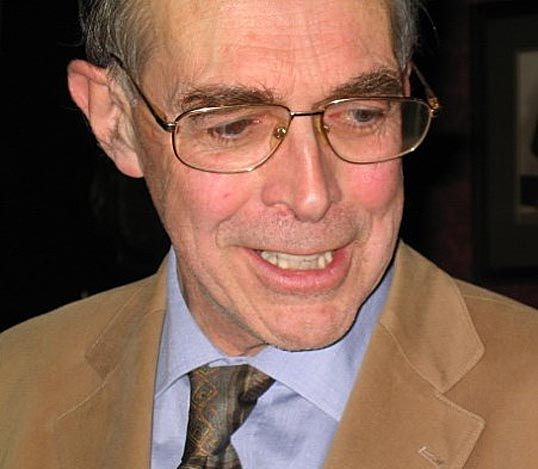

The call to pursue the common good in an increasingly polarised political environment involves understanding meaningful communication and community—behaviour the church uniquely is qualified to model. Here, Professor Oliver O’Donovan excavates the meaning of the term and its relationship with church and state.

Let me begin this exploration of the meaning, and indeed the very possibility, of the common good with the grammar of the term itself.

In a series of like relations between two or more terms, where one term in each relation is constant and the others vary (rAB, rACD, rAEFG and so on), we say that the constant term is common to the relations.

Sebastian Bach, as father, is common to Emmanuel Bach, Christian Bach and Friedemann Bach; Hungary is a common bordering territory to Slovakia, Romania, Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia and Austria; a piece of carrion is common as prey to the birds that feed in it and the grubs that it hosts.

No term can be said to be “common” to other terms except in a stated common relation to them. The common relation does not entail any other relation of the varying terms to each other. Common relations are not only frequent of occurrence but often of little significance.

Typical of human beings, however, and treated as of great moral significance, is a relation in which a common interest generates in those who share it a further reflective interest in one another. We have an abstract noun reserved for this special form of common relation: community.

In speaking of a community we imply, not only a relation common to the participants, but a relation among them. A common interest that a number of people have in a tract of land that they inhabit comes to reflective consciousness as an interest in one another as neighbours. The common interest has itself become an object of interest for them.

Leaving aside for the moment the possibility that this added layer of interest might be competitive, as when we recognise others as rivals for a scarce commodity, community is formed by conceiving an interest in the interest other people have in what interests us. This is the sense in which a good may be called “common”: our interest in it is held reflectively and deliberately in common with others, valued because it is “ours.”

One further terminological step follows at this point. A common interest, now reflected as a mutual interest, can be described as “communicated” – which is to say, held as common. Medieval Christianity acquired the phrase “the common good” from Aristotle and the concrete noun “community” from the New Testament, but its exegesis of these terms, and a rather effective one, was with the verb communicare and its verbal noun communicatio. This focussed attention on the truth that a sphere of common interest required a practical disposition to sustain it.

“Communication” is the readiness to assert a private interest only to the extent that it can become a common interest. Its logic can be summed up in the phrase: “what is ‘mine’ is ‘ours'” – not “what is ‘mine’ is ‘yours'” (which is the logic of bestowal), nor “this ‘mine’ is yours, and this ‘yours’ is mine” (which is the logic of exchange). These logics have their place within the broader logic of communication, but are secondary to it. The private interest must first be located within the common interest, the “I” find its context within the “we.”

And at this point a final terminological step is open to us, which is to add the definite article and speak of “the common good” – the good of a community in itself, which makes communication in these or those special goods possible. To speak of the common good is to speak of an ensemble of goods, a bringing together of interests and concerns that arise within a multitude of people with different interests and concerns.

But this ensemble is not just an aggregate of various concerns; it is the reflective holding of all concerns, whatever they may be, in common. This may be stated intelligibly by saying, after Cardinal Joseph Hoeffner, that the common good is “not a sum, but a new value.” More ambiguously, it may be stated by calling it “the sum of those conditions of social life which allow social groups and their individual members relatively thorough and ready access to their own fulfilment,” for the sum of the conditions of social life is something qualitatively more than the sum of particular interests and fulfilments.

What is ruled out in either case is a bald distributive suum cuique, and, on the other hand, a flourishing of the whole at the expense of its members. Let us be content to say that “the” common good is the good of the community of communicating members, consisting in their capacity to realise fulfilment through living together.

That is the good which is offered to our human species to realise, a cultural good rather than a material one. There are, of course, material goods determining the conditions of our physical lives, which need to circulate in common if there is to be the option of communicating anything else, and “the” common good necessarily includes those communications. But it is not the material goods of life as such that constitute the common good, but the practices of communication.

And if we can say of any limited community of interest that the interest is already and also an interest in communicating it, and if we can therefore say that communication is laid on us as an obligation relative to the pursuit of any interest, what we shall meet when we turn from “any” common good to “the” common good is a categorical obligation. If “a” common good makes a claim for communication overriding our private interest in that good, “the” common good makes communication itself and as such the claim that overrides every private claim. It makes communication the constitutive “interest” of our human moral vocation.

So much by way of the basic conceptual grammar of the term. I now want to raise three doubtful questions about the idea of the common good as it has just been outlined. The first concerns its categorical authority; the second concerns the vis a vis of common and private good; the third has to do with the social forms in which such a common good may be embodied – are they concrete, or universal?

The moral authority of the common good

It could appear idolatrous to claim any good as supremely and overridingly authoritative simply because it is, or may be, held in common. Does community (even interpreted at its widest) have unchallenged possession of the whole moral field?

What then becomes of the private good? And (prior to that question, to which I shall return) what becomes of the transcendent good, the good which cannot be captured in an act of communication, but stands over it as the criterion of its adequacy? Is there not a good that is “good in itself” without being “good for us”? And is there no “good for me” that is not “good for us” – a beauty, for example, that pierces my heart, but about which I can say or do nothing – no concert, no exhibit, no critical appreciation – to communicate what I experience?

To these questions we may add a further one: what about the individual life that is “monastic” in the strict and original sense – namely, devoted to the worship of the good as far as possible to the exclusion of communications with fellow humans? We need not intend to practice such a life, or even to commend it, to feel that it needs to be at least a possibility for human existence so to devote every faculty to the worship of transcendence that ordinary communications fall away as inconsequential.

To defend the common good against this worry, then, we must re-think the zero-sum assumptions about the relations of transcendence to immanence which fuel the worry. The Christian tradition has accomplished this by speaking of an original act of communication, one which overcomes the dichotomy of the “good in itself” and the “good for us.” It has dared to speak of God himself as the supremely self-communicating. Is that meant to suggest that God is exhaustively accounted for by our communications? No; it is simply that our communications find their origin in God’s self-communication, and are therefore open to a radically greater communication than they achieve.

The implications of this approach become clearer through the lens of the late medieval theologian John Wyclif, who, building on the legacy of the early friars, advanced a concept of non-proprietary dominion founded on the act of communication. God’s own lordship over creation, he suggested, was exercised by “communication,” by not keeping his own to himself. Nothing was more characteristic of God than to “lend,” not to give away, since God cannot alienate his lordship of any created thing, but to bring human beings into communicative fellowship with him in the disposition of all he has made.

But our interest in God’s communication depended on our responsiveness to it, and so, in his most famously controversial conclusion, “any and every righteous man is lord of the whole sense-perceptible world,” and in receiving any thing we receive the whole world with it. Communicating the goods of creation with each other, we discover a radical equality with one another in our creaturely relation to God. None of us is the source of a communication to others, for we hold what we communicate from Christ.

The good, then, if we follow this thought, is already a communication, even as it is good “in itself.” Let us express this by saying that the authority of the common good lies in the self-communicative character of the good as such, which cannot be known as “good in itself” without being, in some sense, “good for us” too, a claim on our practical interest that we cannot refuse.

To speak of a good as “objective” is not merely to say that it arises independently of our interest in it (though it does), but that it generates our interest. To speak of a good as “transcendent” is to speak of that in which we are all supremely and essentially interested.

Between the good in itself and the good of man there is a difference. The good of man consists, as the prophet says, of doing justice, loving kindness and walking humbly; but it arises from the self-communication of the good: “He has shown you … what is good” (Micah 6:8). There is a lived analogy: the original good enabling and sustaining the good that derives from it, forming it, requiring it and accompanying it, offering itself to our love, which may take the form not only of desire and gratitude, but of simple admiration and worship, for they, too, are practical interests of ours.

There can be a conceptual error of “hyper-transcendence” as well as the opposite error of totalised immanence. The two, indeed, are mutually supporting, since a good that could not be spoken of or thought about would leave us at the mercy of the wholly immanent. We cannot give to one another in the same measure that God gives to us; but a good that could not in some measure be loved by us, and loved by us together, could not be known as good at all.

The common good and the private good

This solution does nothing to relieve the other aspect of the worry, however, namely that the analogy of the common good sounds the death-knell for the private good – an implication which alarmed Wyclif’s earliest critics, who saw in his formulations an assault on the notion of property.

Such a conclusion would, indeed, be a reductio ad absurdum. For if the notion of a private good is simply a mistake, so is the perception of a contested moral field in which the private jousts against the common and the common claims authority over the private. The phrase “common good” refers, apparently, to a good distinguishable from private goods, a good demanding special respect in certain conflicted situations, especially those of public action. If there were no place in the moral field for a private good, what looked like an important moral truth would be no more than a banal truism. The question is simply how to describe that place within a framework of communication.

A much-repeated piece of encyclopaedia-wisdom attributes to the Scottish philosopher Adam Smith a proposal for the dialectical relation of private and common which proved influential in economic theory and has enjoyed an astonishing revival in recent generations. Crudely summarised: the private good is the only form in which the good can appear to practical motivation; the common good is the form in which it appears to a reflective social science, which observes the workings of providence in weaving together a fabric of common prosperity out of the diverse threads of private ambition.

On the face of it, this proposal is unstable. The proposed relation could be sustained only by restricting social science to theoretical reflections, confining it to a philosophical wonder at what Deus sive natura can do. Once it is granted that social science can have its uses (and what social scientist was ever reluctant to grant that?) and that the private and common goods are not so perfectly aligned by providence as to leave no room for the ingenuity of politicians in aligning them better and preventing the burden of the common from suffocating the spontaneity of the private, we have admitted the common good as a practical motivation.

But if it is so for the politician, why not for the private citizen? If my private ends require alignment with the common good, surely I am the best person to make the first steps towards aligning them. And with this the protected space apparently offered to private interest has disappeared as soon as it was thought of, swallowed up in a generalisable concern for the common good.

If we are to identify a point at which private interest has a proper place, we must surely begin by identifying interests which simply have to be private if they are to be acknowledged at all. Because living bodies are materially individuated, our conscious interest in ourselves as living bodies is individuated, too. However pleased I may feel for the patient in the next bed when he goes home from hospital, it does nothing to satisfy my own interest in getting well.

I may have higher interests that lead me to renounce the interests of my body, to be sure – giving up my last ounce of meal to make a cake for a prophet, perhaps. But if I am to pursue my physical interests, I must eat the cake myself.

This takes us back to some elementary truths about matter and spirit. Bare material entities are as they are; they can be shared, but only by division; consumed, but only by the increase of another body; enlarged, but only by displacing something else. They cannot, except as they are held within the sphere of intelligible things, be related to anything, for relation is a function of meaning.

Communications, which are human acts, involve the sharing of meaning. They have a material basis, involving divisions and tranfers, as when money moves from my own to someone else’s bank account or a sandwich from my picnic basket into someone else’s stomach, but the communicative effect of these motions depends on what was meant by them. If we cast our savings at the apostles’ feet, or offer a sandwich to a neighbour, or explain something to a student, there is a communication – not just a material event, but an act constituted by common meanings into which we induct one another without diminution or loss.

When a grasp of the common meaning is lacking on one side or the other, communication cannot occur. Lazarus may keep close to Dives’s gate for the benefits of economic “trickle-down,” the scraps from his table and the nursing-care afforded by his dogs. But since Dives never means the benefits that come to Lazarus, there is no communication between them.

At this point we must give further thought to the Janus-face of property, which is a paradigm of all communication. Property secures ownership, an exclusive interest of a subject in the possession of a given object, but as soon as we say “exclusive” we imply a third party who is to be excluded. Ownership is always implicitly a social notion; Robinson Crusoe had no need to own anything. It may be asserted by an act of war, when we simply threaten or harass the other party to leave our possession alone, or it may be asserted by a claim of property, which appeals to common terms on which an exclusive possessory interest may be defended.

Property is an element in a social argument, an intellectual form that determines right of possession so as to command general recognition. It secures possession by situating it within a framework of right, freeing the possessor from the need to defend it by the constant exertion of force. But it does so by reference to a common interest enframing and justifying the private interest. If I appeal to the law of property, I concede that the terms on which I hold possession are not mine to determine.

My property, therefore, cannot be “absolutely” mine; however wide the permission to exclude others is drawn, it is a permission, founded in common agreement on possessory right. I own within, and in some sense on behalf of, the community’s understanding. The community limits and determines private interest while at the same time securing and preserving it.

Like an alchemist’s cauldron, then, communication transforms our private interests in the material conditions of life into common moral forms and meanings. Because the physical units of human life are individual, it preserves a dignity of the individual within the social whole. There can be no “we” that does not find points of contact with our various “I”s, but, equally, no “I” that does not depend upon the context of the “we” for its significance. Communication involves disappropriation of the “I” which must step back to allow the “we” to emerge, but also reappropriation, as the “I” receives its self-presence back, preserved and enhanced in the fellowship of others.

This second movement is not adequately expressed by speaking of “distributive justice.” Distribution is the simple reversal of disappropriation. It treats the common as a resource for private enlargement, an unassigned resource waiting for the right owner to make out a title to it. There may, indeed, be justice practiced in distribution, but it is not, as often represented, the paradigm relation of the common to the individual. The strength of the individual does not lie in expropriating the resources of the common. As the early church understood very well, “it is better to give than to receive” (Acts 20:16). By giving to, not by taking from, one receives oneself back in a “second nature” with social strengths and competences for service, authority and effective initiative.

In the light of this we may attempt to reformulate the economists’ wisdom about spontaneous self-interest. All practical motivation seems to imply self-interest in two respects. First, we have an interest in any good we pursue, which must, indirectly, be a self-interest. To be interested in a thing is to acknowledge the bearing of that thing upon oneself. To be interested in a good is to be engaged by it, not simply as a good in itself, but as a good “for me, too.” So even in conferring a good upon another, I see that other person’s advantage as of concern to me.

In the second place, we have an interest in the exercise of our own agency. Agency is an incurably self-reflexive power; we cannot act thoughtfully and considerately without caring about whether and how we are doing so. Augustine frequently observes that when we love a thing, we love our love for it. What we strive for is what we are to become. Yet this implies nothing at all about what we are to seek, whether private or common.

These reflexive interests invite us to understand ourselves as social beings within a community; yet we are also possessed of interests that are not reflexive, pursuing objective goals immediately, without reflecting on the self they asserts. But once we conceive that an impulse to act is our own impulse, we can also conceive that as our own it depends on its relations with others.

We are faced, then, with a decision between two opposed concepts of private interest, reflective and immediate. There is a reflective self-interest in the communication of goods, an immediate self-interest in the acquisition of goods. The one posits other agents as partners, the other posits them as rivals.

The critique of private interest, then, must be brought into sharper focus. The philology of “private” points us to a privatio, which is, on the one hand, “exclusion” and, on the other, “diminution” or “restriction”. Exclusion from, and restriction of, communications takes us to the heart of sin in the social realm. Framed by social communications and put to serve them, as in property-right, exclusion may be a necessary protection of the integrity of the actor, who cannot be the competent subject of an exchange or a donation without an exclusive title to the goods he offers for sale or gift.

But enthroned as a ruling principle, exclusion can only diminish and restrict communications. The sins of the economic realm centre upon “acquisitiveness” – which the Greek of the New Testament calls pleonexia and the Latin tradition of translation arrogantia. It consists in amassing resources only to withhold them from communication, enacting a competition aimed at the exclusion of partners – on which Pope Francis has commented memorably.

Our Western attempts to reconstruct the practice of education, healthcare and social welfare on an economic basis designed for manufacture and retail of material goods have had bizarre and damaging results. And as the scope of ownership is not universal, so neither is the scope of monetary exchange, which floats on the choppy sea of social conditions that are, in the end, merely an aspect of human mortality. Prominent in Jesus’s teaching is the parable of the rich fool who did not understand the limits that mortality set on the power to exchange and consume.

Yet the point we must notice is this: even those transactions that are perfectly amenable to quantification and exchange acquire their meaning for us by being drawn into the communication of higher goods. Those who deal in market-exchange first-hand want more out of the market than buying cheap and selling dear. We like to get our citrus fruit on special, but not so special as to close the supermarket down. We have a longer-term interest in the stability of economic communications, the essential component of which, as the economist J.K. Galbraith understood, is not profit but work. Deeper still, we have an interest in the political order underlying social communications, which we call “justice.” Every offer on the supermarket shelf represents to us some other, more important good: human goods, such as work, rest, community; divine goods, such as creation and preservation.

Not to see the good behind the good, not to perceive each good as a communication with a definite source and content, is the snare in which we are easily taken. The communicative potential of each good can be grasped only as we receive the greater communication offered us by God with himself and with one another. At the very heart of all failures of communication is the difficulty in seeing our social relations truthfully in the context of our human vocation.

State, church and the common good

I have spent considerable time in interrogating the words “good” and “common.” There remains one word to think about, the definite article which so unobtrusively attends the phrase, “the common good.”

The persistent presence of the article in this phrase draws some attention to itself. It poses the question of the uniqueness, and therefore the universality of the common good, a question on which its social and political application turns. There are as many common goods as there are communities, and as many communities as objects of communication. Any person may be engaged with a multitude of them, in the university, the courtroom, the office, the market, the family and so on. But the definite article invites us to think of one – “the” common good, embracing the many. What are we to make of this suggestion?

In answering this question we must bear in mind that we have to do with one concept only, not with every concept that might play a part in our political and social thought. The common good is a rich concept, supported by large claims for its foundational status, which we need neither endorse nor reject here. Three features are present in any appeal to the common good in moral argument:

- A demand is made on behalf of a wider horizon than we would otherwise take note of; it challenges us from the side of a projected universality over against the restriction of our own perspectives.

- Its claim is a concrete one, made by some existing community, to which the obligations we owe can be specified; it makes no demand on behalf of new or undreamed of spheres of communication.

- Its appeal is made to our own social selves on behalf of some community of which we know ourselves to be a part, with no claim on purely altruistic impulses.

In other words, it draws concentric circles around our heads, evoking loyalty to wider communities – whether they are localities, institutions, nations, continents, or even the world – that, seen from where we stand at present, can lay claim on our loyalty. The common good does not support the claim of all possible communications, and those that it does support lie within existing spheres of communication which are capable of evoking our sense of identity.

The common good engages with us on the part of established order – not only the nation-state, to be sure, but any social order that is capable of occupying our practical horizon. It defends the achieved community against the danger of neglect; it demands conformity, summoning us back from distracting ambition, warning against the urge to reinvent our communications de novo. Gaston Fessard was wholly right, then, to combine his reflections on the common good with reflections on authority, and to insist that authority not only served, but “mediated” the common good.

It is not simply the public good, we must note, that makes its claim here against a purely private good. It is an established form of the public good, which makes its claim against all speculative adventures and innovations. A poet may interrupt the composition of a poem, or an aid-worker a shipment of aid to a famine, in order to fill out some tedious bureaucratic form in the name of the common good. It is not that bureaucracy is of greater public interest than an aid-shipment or a poem. But bureaucratic forms stand guard on behalf of the established order of law, the political good.

There is a strong community of interest in maintaining law-governed and predictable communications; they are an essential condition of our freedom. As we reconcile ourselves to the necessity of bureaucratic forms that interrupt real services to the public good, in writing poetry or bringing material aid, we renew our commitment to the political community of interest.

Conservative, but not blindly conservative, the common good may refuse support to proceedings that no longer serve communications of any kind; it may be a rallying-cry to support the slashing of excess bureaucracy or the reform of political structures that fail to defend freedoms. But it cannot be a rallying cry for ignoring established orders of communication altogether.

This makes the supposedly categorical nature of its moral claim more than suspect. Clearly it depends on the capacity of the political sphere so to occupy the horizon of the practical imagination as to appear, for all practical purposes, universal. But only for as long as the political succeeds in doing this can the common good present its claim as paramount, and that can never be for very long, because the moral field is constructed not only of actual but of possible ends, and possibility is always in a position to hold established arrangements hostage. In the light of what may emerge as a possible future, we come to see that loyalties thrust on us as “the” common good are in fact no more than “a” common good.

As in an eclipse, the shadow of the concrete falls across the luminous surface of the universal, but the light will emerge from the shadow. But the idea of the common good itself, by the force of its appeal to universality, has doomed its own concrete manifestations to be transitory. The concrete has no light of its own, and must call upon the universal to illumine it. There is, then, as well as an innate conservatism in the concrete demand of the common good, also a universal that will relativise that concrete demand.

And so there are two misunderstandings we have to be especially on guard against in deploying the elusive and self-transcending language of the common good. One is what we may perhaps be permitted to call “the Prussian doctrine of the state”: the idea of a political organisation comprehensive of all actual and possible communications, which is in itself therefore the concrete universal, the achievement and interpretation of the purposes of God. The universal good may be represented in a form we can conceive synthetically, for practical purposes, by the state or some other established order. But this conceivable form does not anticipate all possible moral demands. Concrete moral demand can always outrun synthetic moral vision; it may call us to do what we do not wholly see. That is the truth of the experience of obligation, the experience of something as required of us which is not wholly, or not yet, self-explanatory and perspicuous.

One of the most memorable features of Gaston Fessard’s contribution is his recognition of the “problem” of imagining the universal common good, and his insistence that it cannot be grasped simply as an extension of scale, whether in existing community, on the one hand, or in the activity of communication, on the other.

The Prussian doctrine of the state can migrate into larger-scale bureaucratic organisations of a multinational or international character. One false universal the Scriptures can acquaint us with is that of empire. In the common good, as Gaudium et Spes sought to remind us, there is a thrust towards the universal, but the true universal is not quantitative, realised by extension of organisational scale, scope or rigour, but qualitative, too, requiring a depth of personal “communion,” as Fessard names it.

The other misunderstanding we must beware of concerns the relation of the universal common good to history. The truth of history is that time is not, as Richard Wagner conceived it in Parsifal, “turned to space.” Language about action in history cannot be assimilated to language about making things. The universal is not an artefact, to be constructed, replicated, copied and so on, with time as a kind of material element out of which it is wrought.

The question of the universal is inevitably a question about eschatology, the “fulfilment of the times.” As this is not at the disposal of human imagination, so it is not at the disposal of human construction. What is realised historically can only be watched and hoped for, refracted indirectly through the prism of anticipation.

Fessard, like many of the non-Marxian heirs of Hegel, walks this ground warily, and only by allusion. But in biblical eschatology we have a tradition of thinking that we cannot ignore, since it presents us with a warning. The future is infinitely more than an echo or projection of the present. Its availability to us is represented in the image of the “sealed scroll” of prophecy, which offers itself to faith and hope, but not to sight. The future must be waited upon, known in the interim through prophecy and promise, in which human freedom has the space it needs to bear its responsibility for the present.

Among the many powers possessed by the state and established institutions prophecy does not count as one, and to the extent that it pretends to that function, it will be a “false prophet,” projecting the reproduction and expansion of the present dispositions of power. The opening of new communications is not something at the state’s disposal; it can only respond to discoveries that excite the community. But the breakthrough of new communications occurs on the scale of the imagination that is spiritually primed to receive them, in parvo.

One of the various things that has been meant by “liberalism” in the past has been the preservation of space for prophecy in a circle of non-state-governed communications. But in what form can prophecy interest us in the undreamed-of future? If it can take concrete form, does it do so in a social or only in an individual way, in the great individual personality, for example, that shapes history, or in the artist or wise man? At the centre of Fessard’s presentation is the claim, made in direct opposition to that made for the Prussian state, that the church is a society that represents the concrete universal.

In interpreting this claim we must introduce a qualification: an alternative established community could only be an alternative state. Though the church must always be an established community, it is not as such that it could play the role that Fessard would assign to it. It can only do that by being the locus of a disclosure of ultimate promise. It is as eschatological hope, embodied in the presence of the church, that the concrete universal breaks through the prevailing common good in order to offer us community in new and transformed guise.

To illustrate this, consider St. Luke’s famous description of the “communism” of the earliest church: “No one said that any of the things that belonged to him was his own” (Acts 4:32). There is, here, an assumption of the good of property as an institution, but also a transcendence of it, to enter a sphere of communications that do not depend on it. This exemplifies the moment of breaking through, where the prevailing common good is dismissed and reconstructed. Luke does not imply that property was merely a unhelpful social fiction which the young community ceased to believe in (as was in fact the case with slavery, but that is another story). In throwing what they owned at the apostles’ feet, and so disowning it, they declared the radical devaluing of this symbolic form of the common good.

The idea of outright gift is paradoxical, as many philosophers have insisted; the alienation of a good can never take us beyond the realm of social interaction and reciprocity. But gift does represent a new initiative in social reciprocity, a point of discontinuity where a fresh input can be made, where what we introduce into the circle of communications is no longer simply a return for what we have already drawn out. In this way, it can radically revalue the forms of reciprocity that prevail in a community, reorienting its communications to their God-given goals.

We know that those who cast their possessions at the apostles’ feet did not “solve” the problem posed by property; by shaping the church as a property-owning corporation, they merely helped property evolve, and the friars, who confronted the problem again in its new form with their ideal of non-proprietorial community, merely helped it evolve further from real-estate liquidity, encouraging the economy of salaries, investments and so on, with which the modern world is familiar.

One could, perhaps, represent these donors of the early church as the progenitors of capitalism. But that would miss the moral point: the setting aside of property, that paradigm of orderly social communication, is the prophetic sign of an overcoming of communication by communication, a breakthrough to that higher level of relationship which Fessard names “communion.” Can we doubt that some comparable breakthrough would be a potent sign from heaven to our increasingly proprietary models of life and justice?

Between past and future

The language of the common good, like the language of property which exemplifies it, is Janus-faced. Looking back it points to a concrete givenness of community, a present and existing form within which we have been given to communicate with others, and which we cannot ignore without great blame. Looking forward, it can invite us to think of a City of God, a sphere of universal community, and encourage us to seek intimations of it from the future. But only so far can it take us. It cannot ease us through the portals of the City of God up the steps of a ladder of dialectical reconciliations.

To the extent that it can open the imagination to be receptive to a further future, it can serve us. But what will take possession of the open imagination? A word of promise from the self-revealing God of the future, to be grasped by faith and hope? Or seven devils worse than those of the past that have been cast out? Nothing in the idea of the common good itself can answer that question for us. Nothing can spare us the task of discerning the prophets.

© Oliver O’Donovan

Oliver O’Donovan is a Fellow of the British Academy and Professor Emeritus of Christian Ethics and Practical Theology at the University of Edinburgh. He is the author of many books, including, most recently, Self, World, and Time: Ethics as Theology, Volume 1 and Finding and Seeking: Ethics as Theology, Volume 2.