Communities need jobs to thrive

In the light of today’s ‘levelling up’ agenda and the imperative to bring meaningful work to places abandoned by globalisation, Andrew Bradstock recalls a story from the 1980s and 90s, where Liverpool’s church leaders collaborated with working people, business and government, paving the way for the regeneration of the city. Their partnership shows how the churches, as good neighbours, can be instrumental in retaining and attracting jobs, enabling families and communities to thrive in the places where they belong.

In 1982, the then Environment Secretary, Michael Heseltine, took the heads of 30 major companies around Merseyside on a bus.

He wanted his guests to invest in the region. Unlike some in the Cabinet – who spoke of leaving Liverpool to a ‘managed decline’ after the rioting in Toxteth – Heseltine saw the city’s potential.

He thought that an influx of new businesses, creating new jobs and new opportunities, would go a long way toward tackling Liverpool’s problems. These included not just an exceptionally high level of unemployment, but poor housing, social tensions and a deficit of hope.

If Heseltine struggled to enthuse his ministerial colleagues, in Liverpool itself were others who also believed in the city and its people. Prominent among them were the Anglican bishop, David Sheppard, and his Roman Catholic counterpart, Archbishop Derek Worlock.

Sheppard and Worlock had been committed to tackling unemployment in Liverpool since they first arrived there in the mid-1970s. Sheppard said it was a ‘proper concern of the church’, since the absence of a job took away a person’s dignity and rendered family life more fragile.

Sheppard was known for advocating a ‘bias to the poor’ (the title of a popular book he wrote in the 1980s), but he also understood the role that business played in the lives of individuals, families and communities.

As a priest and bishop in London he had built bridges with local factories and actively supported industrial mission. In Liverpool he worked with the Manpower Services Commission, whose Youth Opportunities Programme made a huge impact on school leavers in the region.

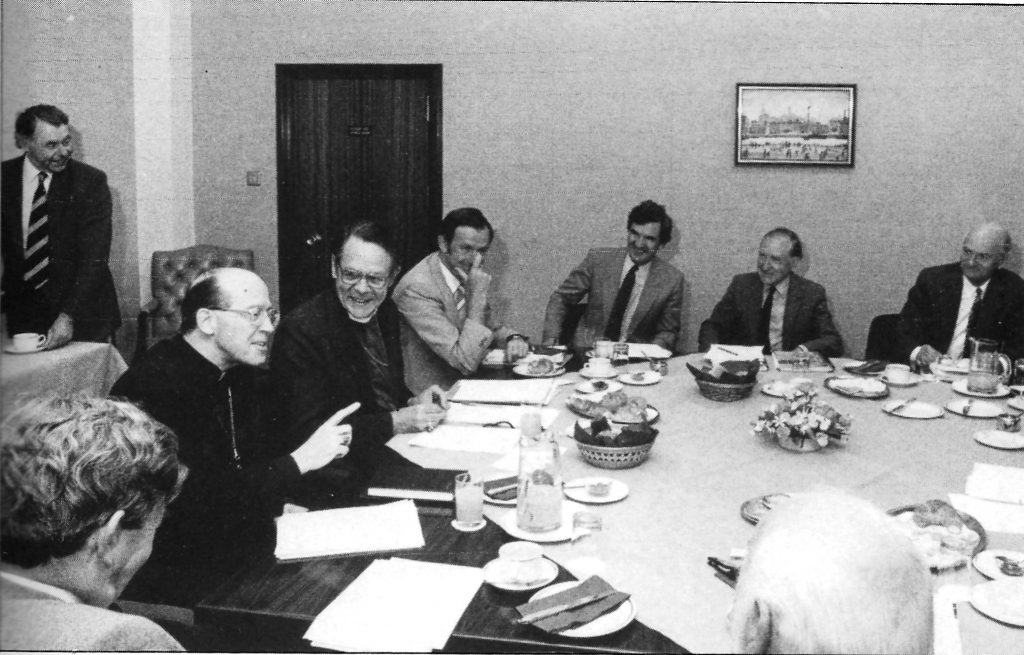

Sheppard and Worlock thought the initial response to Heseltine’s bus initiative had been positive, but few outcomes seemed to be emerging from it. After two years they decided to pick up the baton, inviting local business leaders to a private meeting on Michaelmas eve. ‘Whatever happened to Michael Heseltine’s bus load of businessmen?’ they asked in their invitation.

From this meeting developed what became known as the ‘Michaelmas Group’. Comprising senior managers from the private, public and voluntary sector, government officials co-ordinating policy in the region, and invited individuals with relevant specialist knowledge, the group met for breakfast every six weeks until Sheppard retired thirteen years later.

Michaelmas did not initiate new ventures, rather it helped to enable projects designed to improve the prosperity of the region to reach a successful outcome. The group’s discussions equipped the bishops to put the region’s case to government with more authority than they could do on their own. The expertise in the group ensured they were well-briefed, and ministers knew they were speaking for a wider community and not just the churches.

The Michaelmas Group’s contribution to the regeneration of Liverpool was significant, and the bishops’ role within it pivotal. But they worked in other ways, both behind the scenes and publicly, to attract and keep jobs in the region.

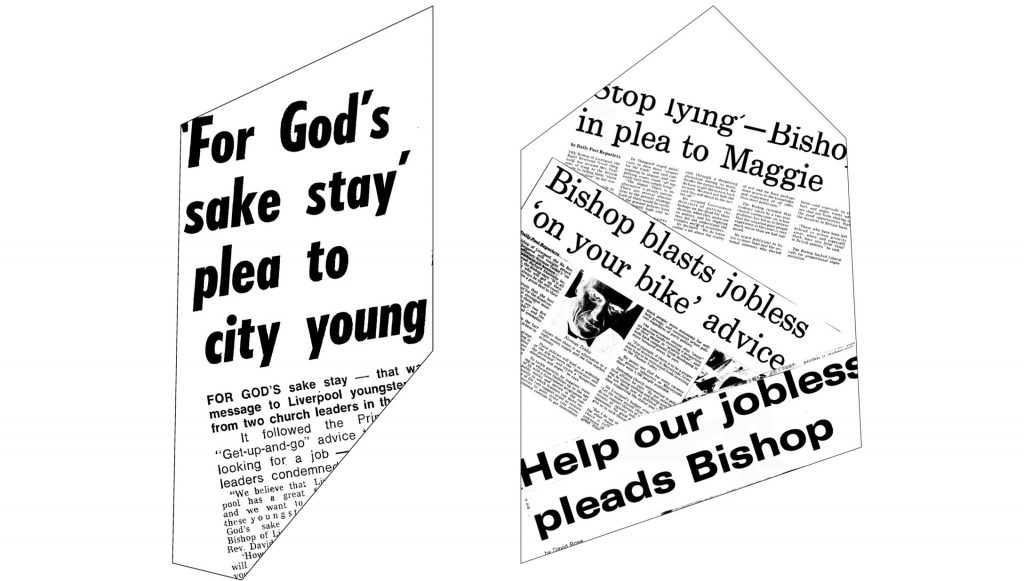

When a company threatened to relocate from Liverpool, leaving local people redundant, they would meet board members to persuade them to change their minds or even join a protest march.

If a company’s closure could not be avoided, they would try to see that it left a useful legacy in the region. They used the media, and Sheppard his seat in the House of Lords, to bring Liverpool’s situation to wider attention.

The bishops helped to create the Merseyside Churches’ Unemployment Committee (MCUC), which monitored the effect of government policies in the region and developed ‘an appropriate understanding of work for the future’.

The churches in the city also did their bit to create jobs. A survey MCUC conducted in the mid-1980s showed that church-sponsored schemes in Merseyside employed 273 full-time and 1,123 part-time workers. Jobs ranged from furniture repair to working with the elderly and on environmental projects.

Some in Liverpool saw the bishops as the only champions they had. ‘Ecumenism?’, one dock worker is reputed to have said when asked what that meant to him. ‘I suppose it means those bishops fighting to keep our jobs.’

At the heart of the bishops’ concern was a conviction that work gave people dignity. It also had social and community value, enabling families and communities to flourish. The bishops would have endorsed the principle of the dignity of work that appears throughout the body of Catholic social teaching. While it is substantially covered in Rerum Novarum (Of New Things) and Laborum Excercens (Through Work), it is summed up particularly succinctly here:

“the solution of most of the serious problems related to poverty is to be found in the promotion of a true civilization of work. In a sense, work is the key to the whole social question.”

Their understanding of the social dimension of work led them to oppose the idea, promoted strongly by the government of the 1980s, that ambitious people trapped in economically depressed regions should move to where work could be found. When people did this, they argued, the communities they left suffered.

On the one hand those communities no longer benefitted from the contribution those who leave might have made, but also their departure made those communities even less attractive to potential investors.

In a letter to the press following Margaret Thatcher’s appeal to young people to ‘get mobile’, the bishops said that placing a higher value on economics than on family, community and pride in one’s city risked creating ‘communities of the left behind’ in some inner city areas.

‘What young people need in the immediate future is the opportunity to train for advanced technologies,’ they wrote. There should be no cutback in schemes providing training for the future, otherwise ‘we will be caught in as vicious circle where businessmen will say, “We can’t bring our business to Merseyside, because there isn’t a sufficient pool of skilled labour”.’

A belief in the importance of community and ‘place’ drove both Sheppard and Worlock. They knew this was what mattered to local people, and this sense of solidarity also flowed from Scripture. Sheppard would often quote St Paul’s dictum about all being ‘members one of another’ (Romans 12.5). In his dealings with business leaders, he would emphasise the well-being of the whole community over the narrow interest of shareholder value.

‘When we make decisions for the well-being of our family or of our company, God’s other children must also go into the scales’, he and Worlock wrote in their first co-authored book, Better Together. This was the essence of the commandment ‘to love our neighbour as we love ourselves’, they wrote. ‘The desire inside a Christian must be about the common good.’

Worlock and Sheppard acted four decades ago, yet their witness to the dignity of work, and its potential to enable individuals and their communities to flourish, can inspire and inform us today.

Andrew Bradstock

Andrew Bradstock is the authorized biographer of Bishop David Sheppard. His book, Batting for the Poor is now available in paperback, published by SPCK. Professor Bradstock is also an emeritus professor of the University of Winchester and a former trustee of T4CG.

More by Andrew Bradstock: Bridge-building leadership and Prosperity and Justice.

If you found this meaningful, you can explore more content like it by subscribing to Together for the Common Good on Substack.