A Personal Church for the Common Good

True solutions to social problems have to come from within, not from outside institutions. This is the view of Personalism, which comes from the heart of the Catholic social tradition, says Colin Miller.

My old friend Travis is a fellow Catholic Worker, and one of the things his small community does is provide hospitality to two or three homeless men. He recently told me the following story.

“It’s a Friday afternoon,” he says, “and I’m getting ready for [our weekly community] supper. The phone rings, and it’s Rick – a new acquaintance who’s come by for these dinners a couple times. Rick explains that he has been befriending the poor, and he has made a new friend who currently doesn’t have any place to stay. And so, he said, ‘since I know you guys deal with this sort of thing, I was wondering if there’s any room for him at your place.’”

So far, you might think, this is the most natural thing in the world – a homeless person referred to a Catholic Worker house. But because I know Travis, I’m pretty sure I know where he’s going with this. He’s not being critical of Rick himself, but he’s concerned about the prevalent mindset in our culture, where we increasingly look to institutions and systems to solve our problems for us.

“It’s a call,” Travis says, “that I’ve gotten dozens of times. And I totally get it – and I’m glad he felt like he could call. Rick knows a homeless guy; we host homeless people; and so he calls us. Nothing could be more well intentioned. So I just nicely explained that we were all full at the moment, but that I would let him know if anything changed.”

As I mentioned, Travis’ Catholic Worker community – a movement founded by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin, one part of which is offering hospitality to the poor and homeless – is small. It’s nothing “official” or “institutional”: it’s just his family and one other who rent some extra space and take in the poor as they are able.

“So,” Travis continued, “what I sometimes really want to say when I get these sorts of calls, is ‘Do you have any extra room where he could stay at your place?’”

Day and Maurin advocated the formation of hospitality houses out of the personal initiative of Christians in a spirit of self-sacrifice. It was to be a way of taking responsibility for the world we find around us without outsourcing it to a charity to do it for us. Catholic Worker houses thus don’t pride themselves on having any special calling or providing a professional social service. Following our founders’ Jesus-centred instincts, we just see ourselves as trying, and usually failing – as Travis would be the first to tell you – to be Christians by living together close to the poor.

The irony that Travis was commenting on was that a little ma-n-pops hospitality house designed to promote personal responsibility would be treated primarily as another charitable agency where professionals take care of our problems. That is how deeply the impersonal, institutional mindset has pervaded our culture.

This way of seeing belongs to the tradition of Personalism, which upholds the significance, unique status and inviolable and relational nature of human persons. Peter Maurin had discovered this from Emmanuel Mounier[1] and introduced it to Dorothy Day. One of its leading philosophers was Pope John Paul II, whose Christocentric worldview centred around the conviction that “the person is a good towards which the only proper and adequate attitude is love.”[2]

Personalism emphasises that human beings should act on their own initiative to form community, care for others, and solve their problems, rather than demanding that institutions do it for them. When we recognise that personalism is the beating heart of any healthy community, it becomes clear why an institutional mindset is so destructive.

The social bonds of any community must exist within that community. If they do not — if the basis of its togetherness comes from somewhere else — then that somewhere else is their true community.

For example, in a workplace, often groups of friends develop. The members are not an independent community but are held together by a commitment to a common employer, rather than directly to each other. The company is the real community. So, when someone takes a different job, it is likely that person will leave the friend group. If they don’t, it’s because the group has found something besides the company to unite them — say, love of music or local beer.

Whatever it is, for the group to hold together, there must be something of personal interest, resulting in intentional and active participation – a shared life. In Catholic language, this is called the common good. It’s the centripetal force — the social bond — of any community. Like a sports team or a choir, a common good means that everyone in the group has an interest in everyone else, because they all have an active, personal interest in the same objectives, and the group is a blessing to all. Common goods are the glue and the energy of healthy communities.

Moreover, to come to know a community’s true common good, one must be intimately involved with its people. Every place and its people are almost infinitely complex. To personally get to know it is the only way to know it at all. You cannot engage the common good from a distance, or by pushing buttons, or through abstract categories. You must live in it. This means that true solutions to social problems will come from within, and not without — from the people themselves, who will have to engage each other in the flesh, in the complexity of local life. This is personalism, and it is deep in the heart of the Catholic social tradition.

Maurin and Day had serious reservations about our culture’s widespread institutionalization. For we tend to assume that if we want to revitalize a neighbourhood or – like Rick – take care of a homeless person we have gotten to know – the first thing to do is look to the professionals — to involve more social workers, lobbyists, doctors, mental health workers, or housing experts. We immediately think of getting people connected, as we say, to the right services.

Yet, what the personalism of Catholic social teaching helps us see is that, with the best of intentions, these services can unwittingly lead communities further from their own personalist pursuit of the common good and toward a growing dependence on external systems. Institutionalized services can displace the interdependence of our natural communities and graft us onto impersonal agencies and systems that then manage large parts of our lives for us.

This is detrimental to communities, because we become more members of those external systems than of the places where we live. The result is that while we might still live near one another, we have little in common with our neighbours, because we do not have to build the common good with them. So, we lose our centripetal force, our glue. Relationships are dissolved. In other words, communities weaken as systems grow strong.

And when communities grow weak, we increasingly look to the state and to professionalized services to do our living for us. We have long been witnessing the growth of an impersonal world where nearly every facet of life is taken up in an agency that manages it and subjects it to formal, bureaucratic processes and procedures. It’s a world where, if you care for the poor, you must be a tax-exempt organization.

Over time, Maurin saw that this hyper-institutionalization makes autonomous, personal action – responding to the homeless ourselves, or even better, from within our neighbourhood or parish – increasingly difficult for us to imagine.

When we get used to living through institutions, making our own decisions in light of the Gospel can become foreign to us. We come to wonder if we can, or even if we should, think for ourselves and act freely, outside of an NGO with a board and five-year plan. We increasingly become a culture of people who feel we need to be supervised, that we don’t count, and that we’re not competent, unless we’re administered by a professional who will manage what we do, keep track of us, and make sure we are plugged in, in the right way, to the system.

At worst, we are left with a society of deeply isolated individuals, connected only indirectly by the agencies that have colonised our lives. The result is a massive dead space, a hole where living together used to be. It’s a hole we are largely filling by staring at screens, consuming content that distracts us from the life-giving potential of our local reality. This is no substitute for the personalist pursuit of the common good.

This is why Travis got worked up. He has spent much of his life as part of one particular, local, concrete and utterly unique common good – and that’s the only kind there is. Its good is his good. And so, it’s personal, because, as true common goods do, it shapes every fibre of his being.

To see Travis’ community as another social service agency is to exactly miss the point of it, which is to ask why we need such agencies in the first place. We need them because we live in a world where it’s normal not to take care of each other. Travis’ life exists as a conscious challenge to that world, and as a foretaste of what Jesus called the kingdom of God. And that’s just what the Church should be.

© Colin Miller

Colin Miller is the Director for the Centre for Catholic Social Thought in St. Paul, Minnesota, USA. A former Episcopal priest, Colin converted to Catholicism in 2016 under the influence of John Henry Newman, Dorothy Day, Peter Maurin and life in a Catholic Worker house. He has been on the staff at the Church of the Assumption since 2019, and lives with his wife and five children at the Maurin House. He has taught at various universities, most recently as assistant professor of Catholic theology at DeSales University in Pennsylvania. He occasionally publishes in journals such as Communio and New Polity. He received his Ph.D. in theology from Duke University in 2010 under Stanley Hauerwas, having previously studied at Yale and the University of Minnesota.

You can read more of Colin’s writing at the Catholic Worker Movement website here

You may be interested to listen to Colin in conversation on the Leaving Egypt podcast, co-hosted by Al Roxburgh and Jenny Sinclair, here

Colin has recently published a book, We Are Only Saved Together: Living the Revolutionary Vision of Dorothy Day and the Catholic Worker Movement – an introduction to the movement for the ordinary person. You can order copies here

NOTES

[1] Mounier, E Personalism (1950)

[2] Love and Responsibility (Ignatius Press, 1993), pg. 41

This story is featured in the Michaelmas 2024 edition of the T4CG Newsletter.

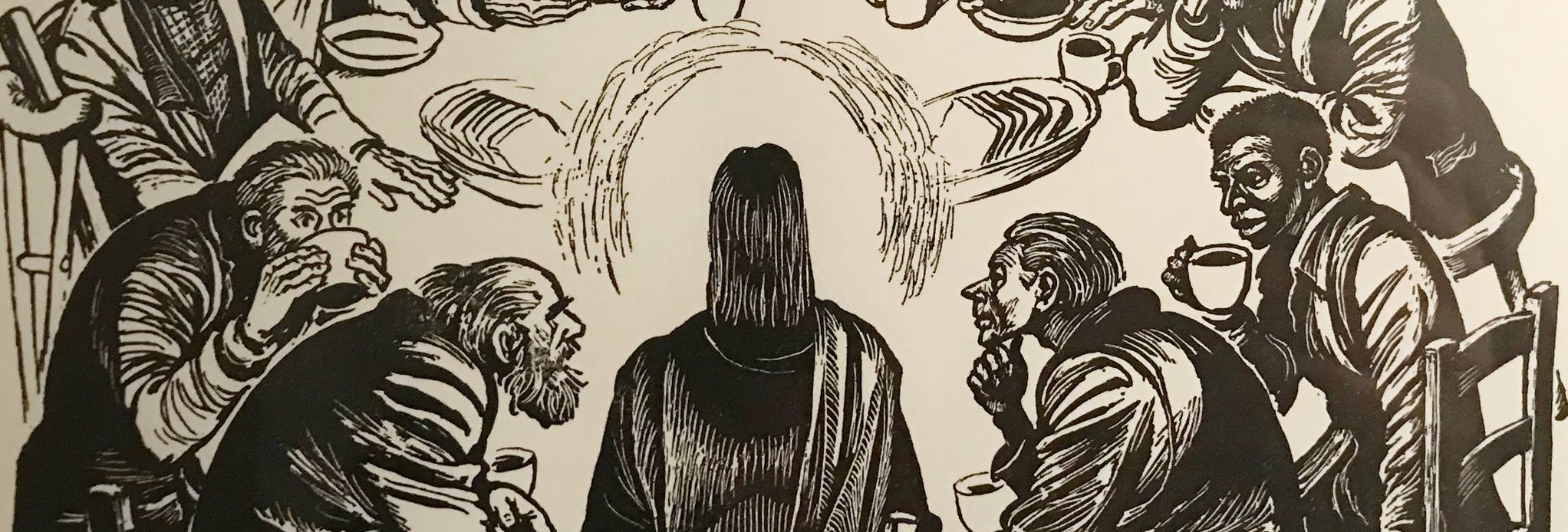

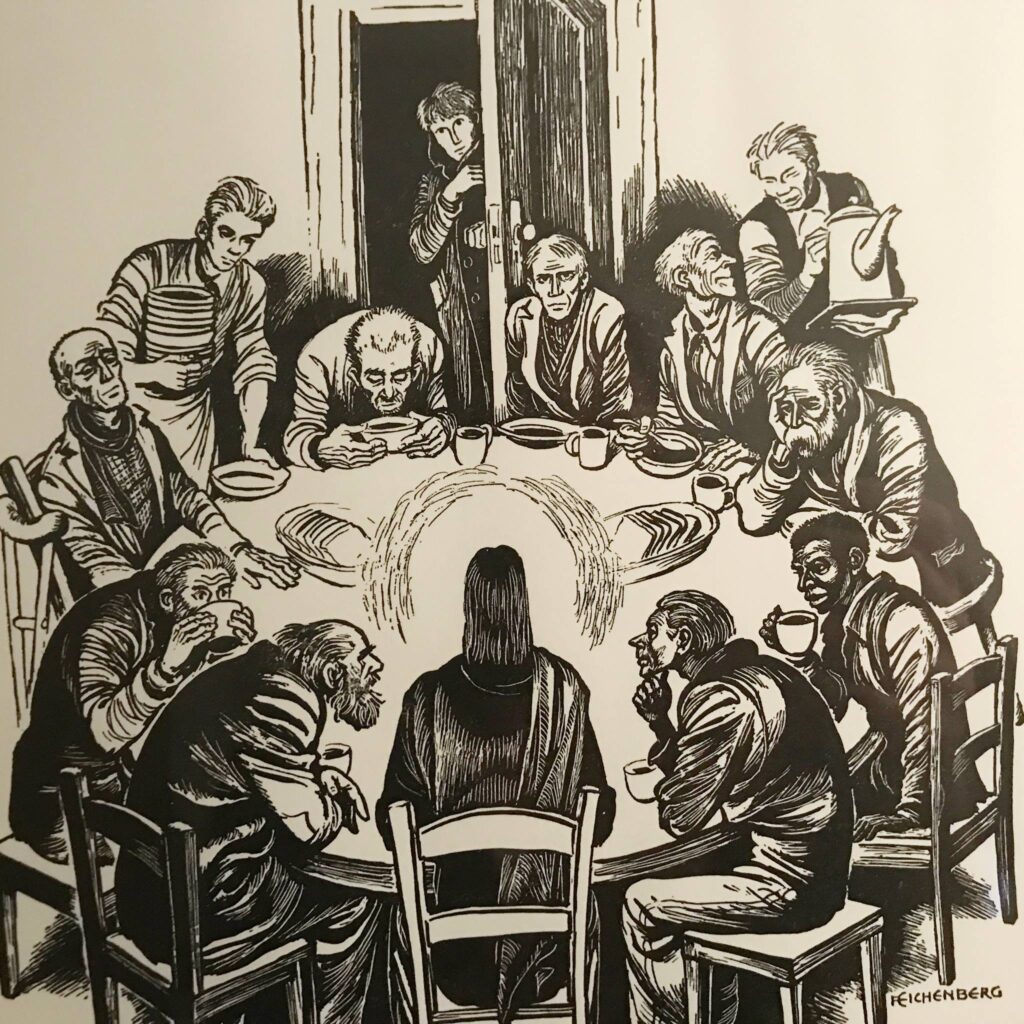

The Lord’s Supper (1951) by Fritz Eichenberg for The Catholic Worker publications

If you found this meaningful, you can explore more content like it by subscribing to Together for the Common Good on Substack.