to live a decent life

An alliance between neighbours

In this age of economic instability, Jenny Sinclair reflects on the Great Dock Strike of 1889 and recalls how dockers, Cardinal Manning, unions and allies across the East End worked together for fair pay and to help their communities live a decent life. In telling the story, she explores the tradition known as Catholic social thought, the framework underlying Common Good Thinking.

Recently I came across a message on social media from young a man who had just lost his job: “I’m no longer needed. I’m willing to do anything. I need a job to support my wife and newborn baby. Help appreciated.” His was not the only one like this. The economic system we’ve had for over forty years has undermined how work is valued.

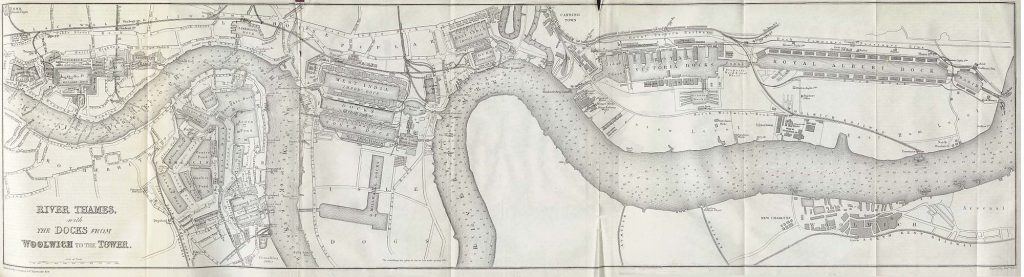

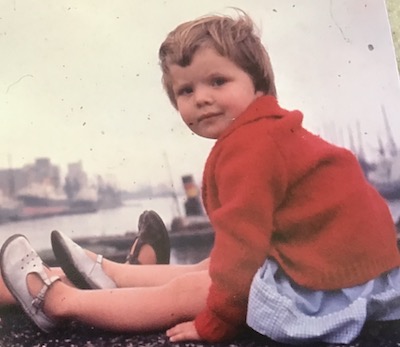

Around the same time I found an old photograph of me as a baby. I was sitting in a pram looking out over the docks in East London. This was Canning Town in the sixties. I grew up in a Dockland Settlement where my dad was the vicar.

Dockers and their families were our neighbours. I learned that being the son or daughter of a docker meant not knowing when your dad would get his wages. Men had to turn up and stand around to get picked for work, which might mean anything from a few hours to a full day’s pay.

Today, unpredictable earnings have become a familiar feature of our economy. That plea from the young father shows how hard it still is to support a family if your work is unstable. Seeing his message brought to mind an event that took place not far from where I grew up, over 120 years before.

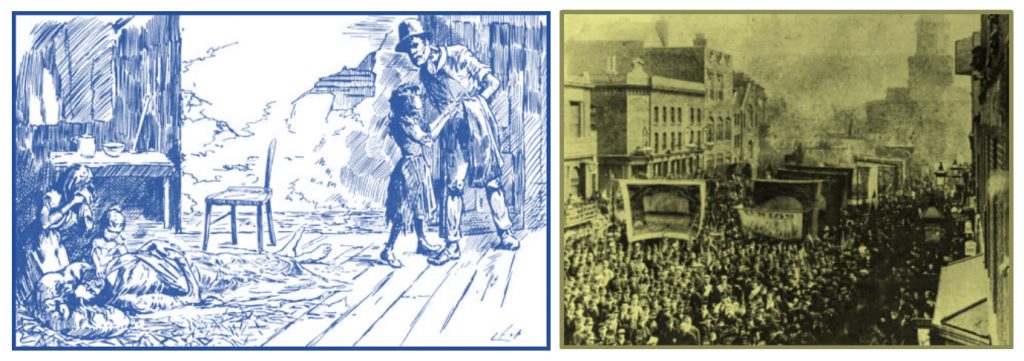

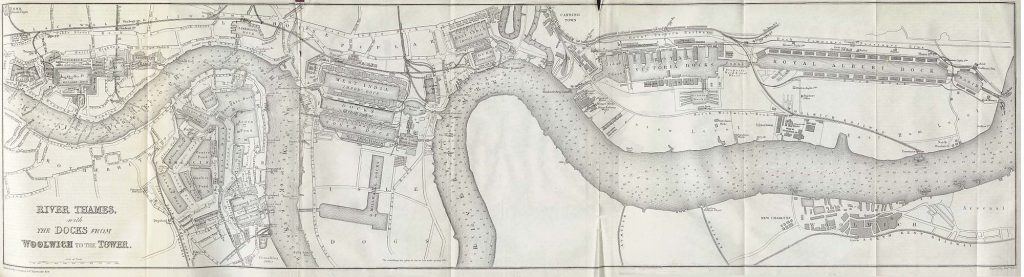

The Great Dock Strike of 1889 happened against rising concern about the living and working circumstances of ‘the working poor’. Families were tolerating appalling conditions. There had been a long fight to gain rights for workers. A series of riots had sparked fears of social unrest, fuelled by sensational press reports about life in East London slums.

The strike began after a dispute between the dock workers and the East and West India Docks Company over a decrease in a bonus payment, known as ‘plus’ money. The strikers, led by Ben Tillett and John Burns, demanded an increase in pay, the abolition of the contract and ‘plus’ systems, and that men should be hired for at least four hours a day.

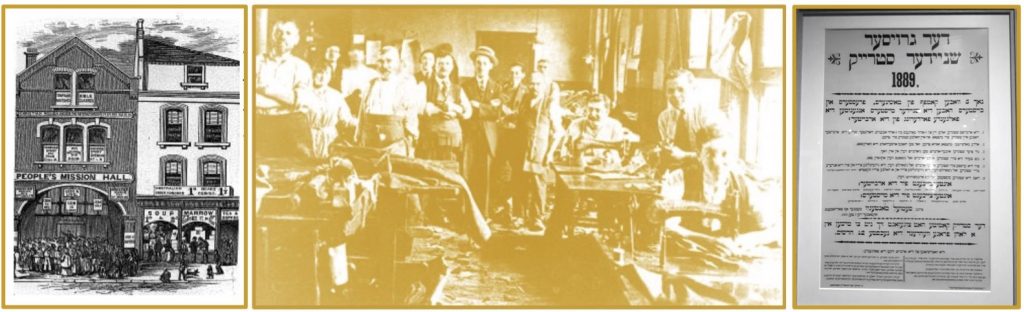

Their action was held at great risk to themselves and their families went hungry. But an alliance emerged to support them, made up of civic friendships long established in the East End, including the Jewish community and the Salvation Army, which provided soup kitchens and raised money for the dockers’ families and children.

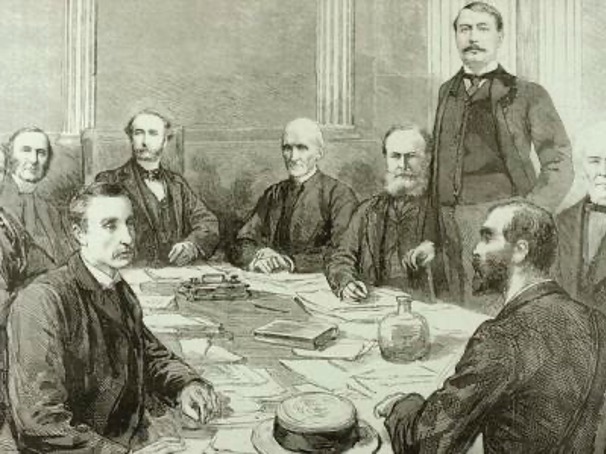

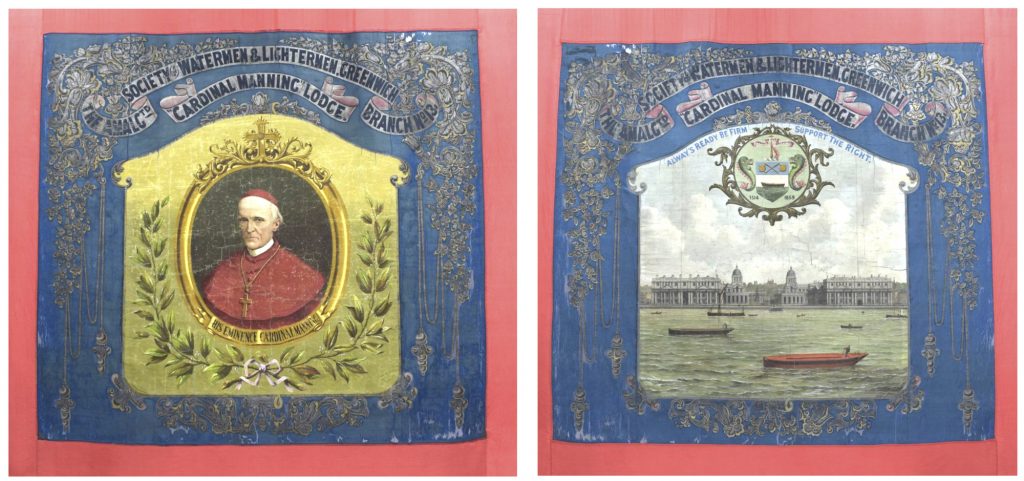

Soon trades across the whole of the Port of London came out in support, along with workers in factories and workshops throughout the East End. There were large, peaceful processions which earned the sympathy of the public. Within two weeks, 130,000 were on strike. One of the busiest ports in the world came to a standstill. Relations between strike leaders and dock managers had reached stalemate. After a month, the Lord Mayor convened a committee. ‘The Mansion House Conference’ was formed to try and broker a settlement. Cardinal Manning, Archbishop of Westminster, who had been involved throughout the strike, was seen as impartial by both parties and agreed to act as mediator.

After lengthy negotiations, the employers met practically all the dockers’ demands. The resolution of the strike became known as ‘the Cardinal’s Peace’.

Manning’s contribution cannot be attributed merely to his mediation skills. He held the trust of both sides. The 81 year old archbishop was the son of a banker and so was fully conversant with the interests of the City. But most significantly he knew his people. He was loved and respected among the parishes in East London. He was the object of working class affection, and had no vested interest other than the flourishing of the communities he served.

During the strike he forged a friendship with the founder of the Salvation Army, William Booth. Their shared concern for the conditions of the working poor comes across in their personal correspondence and in their public writings. The year after the strike, Booth was to write “In Darkness England” and the year before, Manning had published his pivotal article, “A Pleading for the Worthless”.

They were under no illusions about the power of capital and its impact on communities. Manning wrote:

“The capitalist is invulnerable in his wealth. The working man without bread has no choice but either to agree or to hunger in his hungry home. For this cause, ‘freedom of contract’ has been the gospel of the employers, and they have resented hotly the intervention of peacemakers.“

His scepticism about that ‘freedom of contract’ claim resonates today. If he were alive today, Manning would be appalled that we still have zero hours contracts and wages too low to raise a family. He would be defending people on low pay and challenging our dysfunctional system. He would be demanding reform of our political economy. His concern was for the dignity of labour and to see families thrive.

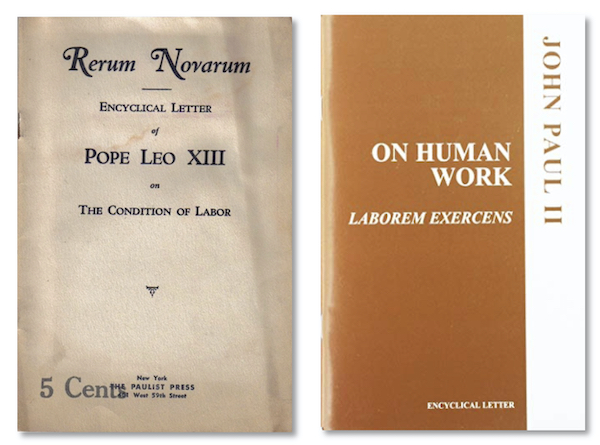

In the ways of the international Catholic family, throughout the strike, Manning had kept Pope Leo XIII regularly updated. Just two years after the strike, Pope Leo would publish Rerum Novarum (Of New Things), a ground-breaking document exploring the theology around the rights and duties of capital and labour. “On the authority of the Gospel”, Pope Leo insisted on restraining the dehumanising tendencies of capital, and set out unequivocally the role of the Church:

“the Church uses her efforts not only to enlighten the mind, but to direct by her precepts the life and conduct of each and all; the Church improves and betters the condition of the working man by means of numerous organizations; does her best to enlist the services of all classes in discussing and endeavouring to further in the most practical way, the interests of the working classes.”

Rerum Novarum is widely regarded as the foundation of Catholic Social Teaching, from which we derive Common Good thinking. Deeply rooted in the Gospel, and transcending party political and ideological positions, it focuses on the principles that enable the human person to thrive.

It explicitly supports the right to form unions, it critiques Socialism and it affirms private property rights. It seeks relational solutions and balance:

“Each needs the other: capital cannot do without labour, nor labour without capital. Mutual agreement results in the beauty of good order.”

This balance of interests gets to the heart of the Common Good. Like the dock strike negotiation, it requires us – the people – to achieve a fair settlement. Later, in 1981, in the heat of neoliberalism, John Paul II was to address the nature of work again. In Laborum Excercens he drew attention to the dignity of work within a sophisticated articulation of political economy. He addressed the forces that degrade the human person. His experience of Soviet Communism and Nazi occupation taught him that the wellbeing of our communities are at risk of being undermined not only by money power, but when government is overcentralised, by state power too.

Capital’s ‘freedom to contract’ carries the risk of commodification: it sees everything including human beings and nature as having a price. But an over-zealous state can dehumanise people too. Since the Covid-19 era we have seen the acceleration of both tendencies. Both have the potential to undermine the flourishing they promise – even more so when they collude. When the state acts in the interests of capital we see a combination of forces that pose a threat to democracy.

We have lived within transactional and individualistic cultures for such a long time, it is easy to forget there is any other way. Somewhere deep in our memory is the tradition of covenant, which holds that agreements should be based on just relationships and the moral order. This is a deeply biblical way of doing things. Within this frame, a negotiation of interests is fundamental.

Manning provides a model for church leaders. He knew his people. He saw them as beloved neighbours. This was a covenantal relationship with people, rooted in a specific place, a faithful promise based on love and respect. When everything else is adrift, there is a need for commitment. Manning’s example points the way for churches today: to build durable local relationships with their neighbours and be prepared to act in solidarity.

The dockers, Cardinal Manning, William Booth and their allies worked together in harsh circumstances to bring about decent pay for local people. Years later around 2001, the same East End communities in the same area were facing similar issues of in-work poverty. They came together as The East London Community Organisation, TELCO, and started to work on what was to become the Living Wage. Inspired by their forerunners a century before, just as Pope Leo XIII had been moved to write Rerum Novarum, their efforts are part of an inheritance of covenantal commitment.

As a baby I looked across the docks at the cranes and ships stretching out for miles. Nearly sixty years on, the landscape has changed almost unrecognisably and the map has been redrawn. But some things remain the same: that young father needs a decent wage to support his wife and newborn baby. Who will offer companionship with this family if not the churches?

The early signs are that Pope Leo XIV will also follow in this tradition, prioritising the dignity of the worker as a central theme of his leadership. We are entering a new era and a new industrial revolution where conditions seem very different. But the old is the new: we are called again to stand in solidarity with our neighbours who wish to live a decent life.

Jenny Sinclair

Jenny Sinclair is founder director of Together for the Common Good.

Like what you are reading? More inspirational content from Jenny Sinclair can be found here: https://togetherforthecommongood.co.uk/news-views/from-jenny-sinclair

Learn more about the Great Dock Strike, Cardinal Manning and Catholic social thought here

You may also be interested in articles about Jenny’s father: A Calling to Build the Common Good and Bridge Building Leadership

Stay Connected

If you found this meaningful, you can explore more content like it by subscribing to Together for the Common Good on Substack.

Silvertown Docks, 1964 [photo: Cathy Huard]